When it comes to Internet Drama, nothing beats the paper letter. Anthropology’s founders did not lead isolated lives. “American cultural anthropology” corresponded with “British social anthropology” and the “Année Sociologique” all the time. I’ve blogged before about Marcel Mauss talking trash about Malinowski with Radcliffe-Brown. But for pure in-your face, the winner has got to be Robert Lowie’s response to A.R. Radcliffe-Brown.

Tag Archives: History of Anthropology

Great anthropologists who fought fascism

Some of you who — unlike me — have not had family members murdered by nazis or had every synagogue in their home town firebombed in the same night may now be learning about antifa for the first time. But although it’s making waves in the media now, antifascist action has a century-long history which includes many anthropologists, who have fought fascism not by writing letters to the New York Times or retweeting an animated .gif but by putting their lives on the line.

As histories of antifascist action document, antifa is a fundamentally illiberal political movement which seeks to oppose fascism by any means necessary — including violence. For this reason, I can’t stress enough that I am opposed to antifa in the United States at the moment because I am opposed to violence, which is both against my values and tactically and strategically against our interests at this point in time given the mood of the country. But in different times and different places the threat of fascism was so dire that violent resistance was necessary. And in those moments, anthropologists acted bravely and with honor. Continue reading

Updated History of Anthropology timeline — now with ‘homepage’!

I (actually, Kerim, who is hosting it) updated my history of anthropology timeline. I’ve also added a homepage for the timeline on my personal website. This page explains how the timeline is set up, what all the tags are, how arcs and individuals are organized, how it is color-coded etc. I’ve also added a tag to my personal blog, so all new updates about the time line can be found there. When I have a chance I’ll upload the source files to my personal blog as well so anyone can download them. If in the meantime you’d like a look, just email me at golub@hawaii.edu.

Clifford Geertz: Ethnographer?

Why was Clifford Geertz such a popular anthropologist? Because he connected anthropology and the humanities? Because he was a great writer? One answer that often comes up is that he was a great ethnographer. I mean, he actually did ethnography. Negara (1980) was a historical anthropology of power that appeared just in time for 1980s-era historical anthropology. Meaning and Order in Moroccan Society (1978) is a massive tome. Kinship in Bali (1975) was technical and dense, hardly the lackadaisical em-dash filled slackfest some people accused Geertz’s writing of being. Peddlers and Princes and Agricultural Involution (both 1963) are vintage New Nations ethnographies. Religion of Java (1960) seems to rise above its Parsonian roots.

But what does it mean to be a great ethnographer? Continue reading

Vale Ben Finney

I was deeply saddened to hear that Ben R. Finney passed away around noon on 23 May 2017. Ben was a professor in the anthropology department at UH Mānoa for over forty five years. He will be best remembered as a founding member of the Polynesian Voyaging Society and a member of the first crew of the Hōkūle‘a that sailed from Hawai‘i to Tahiti in 1976. But Ben was much more then that. A pivotal figure in Pacific anthropology in the sixties, seventies, and eighties, he not only helped rekindle voyaging as a form of indigenous resurgence, he also studied capitalism in the Pacific and humanity in space.

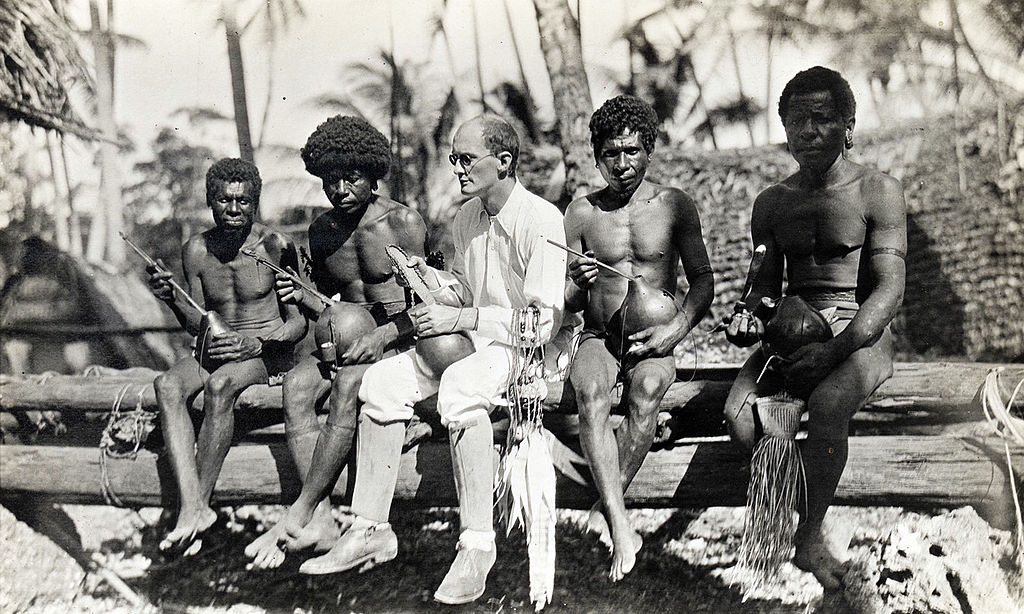

Bronislaw Malinowski: Don’t Let The Cosplay Fool You

If there’s one picture that epitomizes White Guys Doing Research, it’s this one:

The canonical author of the canonical book, naked black people, white guy in white clothes being White — for a lot of people, it’s totally crazy-making. But in many ways, Malinowski was far more more complicated than we given him credit for. There are many people who deserve more criticism for their role in colonialism than Malinowski (just wait for my blog post on Julian Steward). This is not to absolve Malinowski of whatever sins he committed. Rather, it’s just to ask that we remember what he actually did rather than project sins onto him.

The canonical author of the canonical book, naked black people, white guy in white clothes being White — for a lot of people, it’s totally crazy-making. But in many ways, Malinowski was far more more complicated than we given him credit for. There are many people who deserve more criticism for their role in colonialism than Malinowski (just wait for my blog post on Julian Steward). This is not to absolve Malinowski of whatever sins he committed. Rather, it’s just to ask that we remember what he actually did rather than project sins onto him.

Anthropology is an empty pint carton, and our existential projects are the ice cream

Because I regularly teach the history of anthropology, I have thought a lot about classical texts and the shape of our discipline. I also recently had a chance to sit in on a roundtable on Decolonizing Anthropology at #AES2017. Sitting in that panel reminded me of something that Max Weber said. I first encountered Weber’s thoughts on value ideals and concept formation in the 1990s. That was back in the day when Weber used to come over to my apartment and we would smoke out and watch anime. The time I’m thinking of, he got the munchies really bad and ate a pint of Ben & Jerry’s — a pint — before we even got to the first commercial break of the Cowboy Bebop episode we were watching. I was all like: “Freckles” — back then everyone called him Freckles — “Freckles, you just ate a pint of Ben and Jerry’s in, like, two minutes” and Weber just looked at me and said:

“Reality is ordered according to categories that are subjective, in that they are based on the presupposition of the value of the truth that knowledge is able to give to us. We have nothing to offer a person to whom this truth is of no value. We all harbour some belief in the validity of those fundamental and sublime value ideas in which we anchor the meaning of our existence, but the concrete configuration of these values remains subject to change far into the dim future of human culture. Everyone who works in the cultural sciences will regard his work as an end in itself. But, at some point, the colouring changes: the significance of those points of view grows uncertain, the way forward fades away in the twilight. The light shed by the great cultural problems has moved in. Then science, too, prepares to find a new standpoint and a new conceptual apparatus. It follows those stars that alone can give meaning and direction to its work.”

At the time, those words had a profound effect on me, despite the fact that as he spoke them Weber had Cherry Garcia dripping down his beard. They made me realize that anthropology is merely an empty pint carton, and our existential projects — the things we care about — are the ice cream that fills it up. Continue reading

Behold, a timeline of the history of anthropology!

(Update 11 Dec 2016: Up-to-date timeline files are now hosted on github and there is an interactive version of the timeline as well -Rx)

I am extremely happy to announce today that I’m making open access my timeline of the history of anthropological theory. This timeline has over 1,000 entries, beginning with the birth of Lewis Henry Morgan on 21 Nov 1818 and the latest is the death of Roy D’Andrade on 20 Oct 2016. It includes details from the careers of roughly 118 anthropologists from England, France, and the United States. It is designed to be viewed in Aeon Timeline, but I’ve also provided a dump of the data so you can play with it however you like.

History of Anthropology Timeline (98K .zip file on google drive)

“Nor are we big enough to have a place for you as a cameo carver”: Kroeber on why Berkeley wasn’t good enough for Sapir

In my past few walks down the history of anthropology, I’ve tended to focus on white guys being cruel to each other. I thought I’d try to widen my remit a bit in this entry, and look at white guys flattering each other — which involves, in this case, Alfred Kroeber being cruel to himself.

“I know of Malinowski’s despotism”: Mauss to Radcliffe-Brown

The people who fill our theory readers are real people who lived vibrant, quirky lives. It is easy to reduce them to a set of ideas or to a stereotyped, essentialized colonizer. But in fact their ideas — and their colonialism! — were flesh and blood and richly particular.

And they all knew each other.

Consider Mauss’s correspondence with Radcliffe-Brown. Durkheimians both, their theoretical interests allied them against Malinowski. Mauss’s withering, gallic trashing of Malinowski may have more to do with placating Radcliffe-Brown than it does genuine animus. But it also reflects so much else that academia still has: A concern with funding, grudging respect for publication history, trash-talking about a rival’s advising style. It’s all there.

I know of Malinowski’s despotism. Rockefeller’s weakness with regard to him is probably the cause of his success. The weakness, due to the age and the elegance of the other English, those in London as well as those of Cambridge and Oxford, leave the field in England free for him; but you may be sure, even the young whom he protects know how to judge him. There are dynasties that do not last. His big work on magic and agriculture will surely be a very good exposition of the facts. This is what he excels at. And the subventions from Rockefeller for a whole army of stooges which he has had at his disposal will certainly have allowed him to have done something definitive. Only, alongside it there will be a very poor theory of the magical nature of this essential thing. At last he is going to write a great book on his functionalist theory of society and family organization. Here his theoretical weakness and his total lack of learning will make itself still more obvious.

This little glimpse into history is just one of the many open access publications on the history of our discipline that are out there. In addition to the newly-revived History of Anthropology Newsletter there are also the many excerpts and memorial over at the Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford. Thanks to them for making this small, wonderful, slightly terribly little bit of historical kvetching accessible to all!

Malinowski and Hats

The alternate title for this post was going to be “Malinowski, Radcliffe-Brown, and Boas walk into a bar…”. This is a little autobiographical passage from pages 46-48 of History, Evolution, and the Concept of Culture: Selected Papers by Alexander Lesser. In it, Lesser (a vastly under-read and under-appreciated author) describes what it was like to be a graduate student in the 1920s. It’s a fun little vignette that says something about the limits of functionalism… and academic networking! I’ve condensed this account down a good deal — if you’d like to see the full version, check out the book.

I first met both Radcliffe-Brown and Malinowski in 1926 or 1927. It was the first occasion of their both being in New York at the same time. Pliny Earle Goddard was very anxious to have Radcliffe-Brown and Malinowski meet Boas. He believed they would both discover that Boas was driving at the same thing they were driving at, that there really weren’t any fundamental conflicts. Radcliffe-Brown and Malinowski were invited to what was a large living room in Ruth Bunzel’s parents’ apartment, somewhere near Riverside Drive. There were only about ten of us: six graduate students, Malinowski, Radcliffe-Brown, and Boas.

When the time seemed right, Goddard invited Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown to say something. Radcliffe-Brown started off by giving extemporaneously a fifteen minute exposition of what he considered to be the meaning of meaning. It was, from a verbal standpoint a beautiful performance. Boas simply looked at Goddard, and looked at Radcliffe-Brown, and nodded his head. And that was all. Then Goddard turned to Malinowski and asked him if he wanted to say anything, and Malinowski gave an exposition of his concept of functionalism. After he got through with his fifteen minutes, Goddard turned to Boas, expecting him to say something… and then there was utter silence.

After the silence had gone on for as long as I could stand it, I asked a question. I was scare to death, of course. I asked Malinowski if he meant it when he said that every thing, every item in culture, had a vital function. He said, “Yes.” I said to him, “In the back of my hat here’s a little bow which is sewn on to where the seam comes. Now if you go to a store and try to buy a hat, you’ll find it has a little bow on it.” I asked him what its function was. The binding of the hat is sewn together at the back end very tightly; the bow doesn’t hold anything. If it isnt’ there, nothing will happen. And yet if you should happen to buy such a hat in a store, and it didn’t have the bow, the salesman would say, “wait a minute, I’ll have the bow put on.” But what function does it have? Well, Malinowski looked at me and said, “Well….” He thought first of course that maybe it held the hat together, and I showed him it didn’t. So then he said, “Well, maybe it’s decorative.” I said, “How? You can’t even see it.” We went on like this, for some time, but he finally said, “Oh, I’m interested in important matters.” He simply dropped it.

Now, where did I get this item? I happened to be indexing the first forty volumes of the Journal of American Folklore – that’s how I was earning my way through Columbia, for fifty cents an hour. If you start trying to index a thing like that believe me, as you go through a volume it becomes damned boring. So every once in a while, you say: “Oh, what the hell, at fifty cents an hour I’ll read a paper.”

There were several papers by a man named Garrick Mallery. He was an American ethnologist, and he was particularly interested in survivals. In regard to the hat bow, his explanation was that this was a survival of something which had once been more functional. At the back end of the hat ribbons were attached, and one wore the hat with ribbon streamers; style had gradually dictated that these become smaller and smaller, until they were finally stuck up inside the hat, and disappeared into the bow. So much for hats and Malinowski.

Anthropology and the MacArthurs

The 2016 MacArthur Fellows were announced yesterday and — unlike some years — there were no anthropologists on the list. Established back in 1981, the grant was intended not to find “geniuses” (despite the fact that its nicknamed the genius grant) but rather “talented individuals who have shown extraordinary orginality and dedication in their creative pursuits and a marked capacity for self-direction. This year no anthropologists made the cut, but this isn’t how it always goes. Continue reading

Paul Friedrich, Dennis Tedlock, and Generational Change in Anthropology

(update: I incorrectly spelled ‘Tedlock’ in the title of this post when it first went lived. This has now been corrected. Apologies.)

It seems like I’ve been writing a lot of obituaries lately. Between Elizabeth Colson, Edie Turner, and Anthony Wallace and Raymond Smith, I’ve spent a lot of my time thinking about the past. Now, in close succession, we have also lost Paul Friedrich and Dennis Tedlock. It’s sad to record these passings, but I take some consolation in the fact that the people we remember have been so productive and matter so much to the people who mourn them — the world is richer for them having been in it. But in remembering these two today, I also want to talk briefly about how our discipline is changing, and what these demographic shifts might signal for anthropology’s future.

Vale Elizabeth Colson

When Elizabeth Colson passed last month at the age of 99, anthropology lost one of its preeminent figures. Colson was a unique figure in many ways: She straddled the English and American anthropological traditions, rose to prominent positions of authority at a time when anthropology was still largely a men’s club, and exhibited a devotion to her research that few can match: According the Facebook post I was able to find confirming her death (thanks Hylton), Colson died and was buried in Africa.

Vale Edith Turner

Edith Turner — Edie as she was universally known — passed away on 18 June 2016. Perhaps the quickest and least accurate way to describe Edie is “Victor Turner’s wife”. But her importance in anthropology is pretty much totally erased by that description. Edie was a tremendous influence on Vic, and all of his work should be read with the recognition that there is a silent second author on the piece: Edie. But even reducing Edie to merely a co-author of some of the most important anthropology ever written doesn’t do her justice. Edie outlived Vic by 33 years, producing her own brand of anthropology with flair and originality. Edie produced around five books between Vic’s death and her passing — that is to say, after she was sixty-two years old, an age when most people are on the verge of retirement! In them, she crafted an audacious, unapologetic anthropology of religion that parted ways with secularism, science, and over-seriousness… and never looked back.