On Tuesday May 17, 2016, SSRN announced that it was being acquired by Elsevier. SSRN, the Social Sciences Research Network, is a widely used repository of scholarly articles that can be uploaded and downloaded by anyone. It is “open access” (that’s in quotes because SSRN’s approach to OA has always been partial and peculiar, and Monday’s news confirms that perception). Elsevier is, well, if you don’t know who Elsevier is, none of this will make sense to you.

All posts by ckelty

Thoughts on AAA15, Denver, and a “Rawlsian” Internet.

Like many of you, I am just back (and not nearly caught up) from pop-art obsessed Denver. Another AAA, another 2000-person business meeting. Just finished converting my nametag holder into a duvet cover. Also: the parlimentarian.

Rex captured some high and low points–ever the participant observer. Carole (the local) can pull rank and can correct us, but I just want to say that Rex didn’t spend nearly enough time on 16th street if he thinks there wasn’t high calorie cheap food available. I won’t say “good”, but the calories were in abundance.

I feel I can judge Denver because I grew up visiting my relatives there: Wax Trax records is still going strong, hallelujah, Elitch’s gardens has moved from the old-school high-liability zone of my youth to a chamber of commerce immagined dead zone of high profit near downtown, and the mountains are still, by an order of magnitude, thee most. Despite the current fame Colorado Springs is experiencing—which puts the state squarely back in the violent middle America most anthros were probably expecting, but narrowly escaped given the unfortunate regularity of the madness, Denver is in fact a distinctive American place. It’s not very diverse racially, to be sure, but it is distinctive: in the blocks around the convention center there was a definite mix of white lower class, middle class marijuana tourism, ostentatious 1%-er development, overdressed anthropologist and bearded hipsters on loan from williamsburg/highland park. Also, did I mention the parliamentarian?

Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist SM?

Hey folks, Kelty here, Savage Minds blogger, demeritus. The AAA is coming up and with it several celebrations of ten years of Savage Minds! It is also about ten years of Social Media. It’s an Era! It’s a Decade! It’s time for reflection! Which we will do at the excellently early hour of 8am on Saturday morning, on the panel “Teh Internet and Anthropology: Ten Years of Savage Minds”, organized by Alex Golub, chaired by Alex Golub, and with Alex Golub as a discussant.

I know all my fellow Alex Golubs are excited (as are Kerim Friedman, and Carole McGranahan, and Ryan Anderson and Gabriella Coleman), but I have a problem they do not have: I have nothing interesting to say.

Fortunately, this is not the same thing as there being nothing to say–because what I’d rather do is channel the beast itself: I think Savage Minds should be on the panel! How can we bring SM to this small, closed, early morning panel and rub the publics of SM up against the private parts of the AAA. Oh. That sounds weird. I don’t want it to be weird.

Anyways, I’m issuing a small challenge to those who still gather here in and around Savage Minds… pretend it’s 1784, and Savage Minds is called Der Berlinische Monatsschrift, and the question goes like this:

“What difference has SM made to the discipline of Anthropology?”

Some rules for answering this question:

1) I deliberately say SM, because I mean both Savage Minds specifically and Social Media generally. Both issues are on the table, since it is “The Internet and Anthropology.” You can, if you wish, also read Sado-Masochism for SM, but that’s weird, and we are trying to stay away from that.

2) by discipline, I mean the core pedagogical values of the discipline; the way anthropology’s problems and methods are talked about, taught, and performed now, as opposed to 10 years ago. (Not so much the departments, the money or the people, the journals or the scholarly societies, relevant though they may be).

Answers can come in any form–from 140 characters to a comment to a poem to a snapchat that I will probably never see, to a 10,000 word excursus (no, actually, that would be weird, cf. above). But my goal is to collect them and to make the opening 15 minutes into monstrous, anthroporific, wake-up extravaganza by a collective subject called Savage Minds/Social Media. Do you have an answer? Kant you say what it is? Represent yourself Savage Minds!

Continue reading

Reader rights and author rights at Cultural Anthropology

The latest issue of Cultural Anthropology (the last issue edited by Anne Allison and Charlie Piot before until the end of the year when the editorship moves to James Faubion, Dominic Boyer and Cymene Howe) has a bunch of great articles on Open Access (as well a fantastic article by Joe Dumit about a classroom assignment called “The Implosion“). There is a really detailed and wonderful article about CA’s former managing editor Ali Kenner about all the work that goes into making a journal like CA work. Fellow Minds blogger Matt interviewed the new Managing Editor Tim Elfenbein who is already doing great new things with the journal, and other fellow Minds blogger Ryan interviewed Jason Baird Jackson about the state of OA today. There is also an excellent article by non-anthropologists Kevin Smith and Paolo Mangiafico from Duke Library about the challenges of OA in the University context today.

In the course of preparing the interview that I did in the same issue, I discovered that even though the AAA is making Cultural Anthropology open access, they are not doing it the way everyone else does so–by applying CC licenses to the articles. I explain this more in a blog post on the CA website, but I think it is important for people to recognize that OA is not just about reading, and not just about Author’s rights but about readers’ rights as well–something we in anthropology should be especially sensitive to.

Open Access Success, California style.

(It took me a while to figure out how to post here since Savage Minds is now in a permanent state of exception. We are all Agambenians now, apparently.)

Two weeks ago the University of California system-wide Faculty Senate announced that they have passed an open access policy for all 10 campuses. The policy covers 8000 tenure-track faculty, and as many as 40,000 papers annually, making up 2-3% of the worldwide scholarly journal content. More details (and some videos of me looking really tired) are here.

This is a major success. It’s a huge university system, with an unusually powerful federal faculty governance system, and getting any organization that large to do anything forward thinking is itself a triumph, and I’m proud to have been part of it. The policy commits faculty to making their work available using the California Digital Library’s eScholarship platform, or any other open access repository. It will begin on Nov. 1st, and will roll out first at UCLA and UCI, in addition to UCSF which passed a policy in May of 2012. Continue reading

Leisure Class as anthropology class

I don’t ever teach an Intro to Anthropology, a fact for which I wake each day thankful and perform several ritual ablutions and say long meandering prayers to as many culturally specific deities as I can remember. But if I did, I would start with Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Leisure Class. In fact, I might even make it the only text for my awesome four-field anthropology class.

Economists think the book belongs to them–or those few evolutionary and/or institutional economists who take the book seriously (Geoffrey Hodgson leads this ragtag bunch of misfits and loyalists yearly into battle). But the book is anything and everything but economics. In fact, the book is a weird and wonderful combination of anthropology, economics, psychology, sociology and speculative phenomenology. One of the reasons people might not grok the fundamental wackiness of this book is Continue reading

Happy Valentines Day, public

FASTR (Fair Access to Science and Technology Research Act) is the newest revival of legislation designed to open access to federally funded research (used to be called FRPPA). Currently only the NIH requires open access to federally funded research (and this only after 12 months), but this bill would extend it to all federally funded research (for budgets over $100 million) and shorten the time to 6 months. Go forth and support it, it is good for everyone. The public will be your valentine if you do.

You should pay $$ for open access. Help the AAA figure out how.

AnthroNews at the AAA has a post about the challenges facing it’s publications program. It doesn’t suck. Here are five things to think about:

- Would you pay higher membership fees if you knew that what you were paying for was a robust open access publishing program? You should, and not out of altruism, but because it will cost you less than it would to buy all the subscriptions your library is going to cancel in the next year or two.

- What exactly does the AAA pay Wiley-Blackwell to do? What besides “improved ISI impact factor rankings” do they give us, and can we buy the same services elsewhere for cheaper?

- Folks at AAA keep asking “Who is to bear the costs of Open Access”? Why is this so hard to answer? Given that there are no “customers” for AAA publications other than academics, the answer is dead simple: the people who already pay the costs of closed access must choose to pay the costs of open access. Remember that the money we get from WB (“royalties! hooray!”) comes out of your other pocket while you are not looking–i.e. your library, which pays the ever-increasing subscription costs. Or not.

- Why does 50% of the royalty revenue from Wiley Blackwell go to Anthropology News and American Anthropology, while the other 20 publication get the other 50%? Shouldn’t we rethink this allocation? Why is it so hard to find out where this money goes?

- “Posting comments is a benefit for AAA members”? Really? Honestly? I’d love to leave a comment–even a supportive one in this case– but apparently one must “leave your name so we can verify your membership and approve your comment.”

How much does publishing really cost? The Long Answer.

There is an article in a recent issue of the Guardian reporting on statements by the editor-in-chief of Nature, Phil Campbell. It says two amazing things. The less amazing thing is that he says open access is inevitable. The more amazing thing is that he says that the cost of to publish in Nature or Science is “in excess of $10,000” per article.

Let me just write that one more time for people who don’t speak arabic numerals: in excess of Ten Thousand Dollars for a Single Article in Nature.

Now Nature is a pretty phenomenal publication, and I don’t doubt that it is expensive to produce, but I think most of us cannot fathom what it is that these publishers are doing that might result in such costs. $10,000 is, from the perspective of most anthropologists, is what it costs to do the research not what it costs to type it up. How can this be?

I can answer this. At least, I can tell you what the Good and the Bad reasons are for these costs, and why we should consider paying for the good reasons and stop paying for the bad ones.

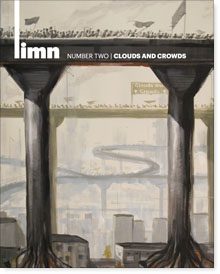

The reason I can answer this is because I now publish an magazine– on the web and in print, called Limn. It’s free (as in speech) but it is also for sale (it’s beautiful, btw, and you should buy one, since I’m here explaining to you why you should). The three issues (comprising two print issues and about 30 articles) and website combined have cost about–wait for it–$10,000 to produce. Most of that has gone to the labor of a developer and designer (and anthropologist) who has done an absolutely amazing job. 30 short articles (about 2000 words on average), works out to less than $250 per article; probably less, since that price includes the start-up costs of creating and designing a going concern from scratch. The money came from a combination of research accounts, in-kind support from departments, and my pocket.

There is a huge difference between $250 and $10,000. And really the comparison between our little experiment and Nature is not fair to either side. However, I do think it’s fair to make a comparison with the AAA because the AAA is insisting that publishing is so expensive that switching from subscription to open access will ruin them. But from what I can tell, publishing in a AAA journal is significantly cheaper than $10,000, so it should be within reach of an alternative model. In January of this year, Oona Schmid, director the AAA publications program at the AAA gave a talk at Columbia (which also included our own Alex Golub as commentator; Oona starts at 13.10; Alex at 58.50). Based on her presentation and the AAA annual report from 2010, I have the following facts:

Continue reading

Not that kind of “living in the past”…

This is bad. The Archaeological Institute of America has published a statement in its popular magazine opposing open access. And by opposing, I mean totally hating on the concept.

We at the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA), along with our colleagues at the American Anthropological Association and other learned societies, have taken a stand against open access. Here at the AIA, we particularly object to having such a scheme imposed on us from the outside when, in fact, during the AIA’s more than 130-year history, we have energetically supported the broad dissemination of knowledge, and do so through our extensive program of events and lectures for the general public and through our publications. Our mission statement explicitly says, “Believing that greater understanding of the past enhances our shared sense of humanity and enriches our existence, the AIA seeks to educate people of all ages about the significance of archaeological discovery.” We have long practiced “open access.”

Really? No. Really? But wait, there’s more:

While it may be true that the government finances research, it does not fund the arduous peer-review process that lies at the heart of journal and scholarly publication, nor the considerable effort beyond that step that goes into preparing articles for publication. Those efforts are not without cost. When an archaeologist publishes his or her work, the final product has typically been significantly improved by the contributions of other professionals such as peer reviewers, editors, copywriters, photo editors, and designers. This is the context in which the work should appear. (Almost all scholarly books and many articles lead off with a lengthy list that acknowledges these individuals.)

And then there is this:

We fear that this legislation would prove damaging to the traditional venues in which scientific information is presented by offering, for no cost, something that has considerable costs associated with producing it. It would undermine, and ultimately dismantle, by offering for no charge, what subscribers actually support financially—a rigorous publication process that does serve the public, because it results in superior work.

I was going to write a really scathing response about how evil this is. But really, I don’t think i can do it. President Bartman and the archaeologists are running scared, just as the AAA is. The issue comes down to something much more fundamental than open access, and I direct this at faculty, students and other members of scholarly societies:

Do you want your scholarly society to survive?

I mean this honestly. I, for instance, do not. I no longer give a flute about the AAA. I’ve tried my hardest to make the error of their ways visible to them, but failed. I’ll miss the meetings and the swag, but they now do nothing else but suck money out of my university library and give it to Wiley Blackwell. Game over.

But I undestand if you don’t feel that way, and if you don’t then it really is a problem that our scholarly societies can only exist by making our research less accessible and available. We need to find another way.

Here are some issues to consider if you are an archaeologist (or belong to any scholarly society):

Continue reading

Where your money and your articles meet

Continuing the spate of renewed enthusiasm for diagnosing the mess we are in, here is a fantastic article by David Rosenthal, currently at Stanford library. It’s part of a workshop on “The Future of Research Communication” for which he was asked to diagnose what’s wrong. It’s cogent and complete in the form it currently takes, I look forward to the report.

Just a few nuggets to get your outrage on:

- Rosenthal clearly diagnoses one of the problems with the “bundling” strategy (i.e. giving deep discounts for buying multiple titles, instead of choosing what is needed by a given institutions) that large and small publishers have aggressively pursued. His suggestion is that it is responsible for the dilution of quality, and the proliferation of outlets that might otherwise starve for lack of interest.

-

In terms of peer review, which is done primarily by the same conscientious people over and over again (you’re welcome): “In 2008, a Research Information Network report estimated that the unpaid non-cash costs of peer review, undertaken in the main by academics, is £1.9 billion globally each year.”

-

Wiley-Blackwell’s 2010 results show their academic publishing division had revenues of $987M and pre-tax profit of $405M, a gross margin of 41%. The parent company’s tax rate is 31%. On the same assumption the net profit is $280M; 28 cents of every dollar of subscription goes directly to Wiley’s shareholders.

There is much more to make you weep…

Ethnocharette: The Post-It Note as technology

Just received news of this experiment at UC Irvine: Ethnocharette. Keith Murphy and George Marcus have documented a process of exploring a text (Robert DesJarlais’ Shelter Blues) through a studio-style design process. The website details the process and the results. It’s always a bit hard to understand exactly how this kind of process works for people or how it’s different from a seminar discussion, for instance, or the creation of “reading responses,” but given the smiling people in the photographs, it looks like it worked. Having spent my fair share of time struggling with new media technologies from wikis to blogs to collaborative editing, there is something nice about exploring the limits of a very simple tool: post-it notes. I’ll try this out in my classes this year I think…

Just received news of this experiment at UC Irvine: Ethnocharette. Keith Murphy and George Marcus have documented a process of exploring a text (Robert DesJarlais’ Shelter Blues) through a studio-style design process. The website details the process and the results. It’s always a bit hard to understand exactly how this kind of process works for people or how it’s different from a seminar discussion, for instance, or the creation of “reading responses,” but given the smiling people in the photographs, it looks like it worked. Having spent my fair share of time struggling with new media technologies from wikis to blogs to collaborative editing, there is something nice about exploring the limits of a very simple tool: post-it notes. I’ll try this out in my classes this year I think…

The Anthropology of Freedom, Pt. 5

I’ll stop with this one, I promise. But it is in some ways where I should begin. That freedom is an interesting problematic obviously has little to do with whether or not anthropologists can wield it as a concept (that’s just me deferring to the putative audience here). Rather it is a simple empirical fact that freedom–both as slogan and as a thing–is relentlessly present in global society–and especially in the domains of high tech science and engineering. The ideological use of the slogan to brand just about anything is (should be) fair game for many different scholars of contemporary discourse (see e.g. Wendy Chun’s work). But as a starting point, consider only the image to the right, which collects 9 pages of logos that use “freedom” to sell something.

These uses come from both the left and the right, and they have a certain visual consistency to them: images of upheld arms, liberated birds, broken chains are nearly ubiquitous. When a logo emphasizes a flag, a gun or an eagle it is more obviously right-leaning, when it uses a sans-serif font, the color green, or a raised fist, it is more likely a left-leaning cause. Revealingly, the same experiment with the word “liberty” is much more uniform in the use of red, white and blue, the statue of liberty (especially her spiky hat… what is that called anyways?) and only occasionally a broken bell. This analysis could all be done much more expertly, I’m certain, though it hasn’t really been. (Though I can’t resist mentioning a smorgasbord of a book by Svetlana Boym which is obliquely engaged in such a project of cultural and visual analysis).

But what such an analysis tells us is that freedom has a particular ideological role in the process of our collective deliberations and arguments in the global media-scape. In it’s most cynical version, Continue reading

The Anthropology of Freedom, pt. 4

But that being said, there are in fact a lot of other “Anthropologies of…” which border very closely on anthropology of freedom, and I want to dwell (at too much length) on one of them here: the anthropology of ethics. There is another one going by the label of an “Anthropology of the Will” which will have to wait until whoever has the book checked out returns it to the library, cause there is no way I will pay $55 for it, thank you very much Stanford University Press. There is also the “Anthropology of Happiness” which insofar as freedom is a means rather than an end might be something anthropologists do study. I’m much too pessimistic for that.

But the anthropology of ethics has finally arrived. This year has seen the publication of two books: Ordinary Ethics, (a semi-reasonable $30, $21.99 on Amazon) ed. by Michael Lambeck, and James Faubion’s An Anthropology of Ethics (ditto). The former is a great collection of essays that includes both anthropologists and philosophers (and includes one from Faubion), the latter is likely to appeal to me, Rex, and like 5 other people, which says nothing about how awesome it is, but rather, indicates a perhaps perverse pleasure in being inside James Faubion’s brain. Nonetheless, both of them lay out some problems and concepts for an anthropology of ethics in rigorous and satisfying ways.

It should be said that the “anthropology of ethics” referenced here probably means many things Continue reading

The Anthropology of Freedom, Part 3

“The time is now ripe for anthropologists to consider the concept of freedom and the empirical manifestations of freedom in culture. What more significant and urgent task is there for the anthropologist than that of launching a concerted inquiry into the nature of freedom and its place and basis in nature and the cultural process? Such an inquiry would provide in time a charter for belief in those values and principles indispensable to the process of advancing culture and to the ideal of a democratic world order dedicated to the development of human potentialities to their maximum perfection.” (preface to The Concept of Freedom in Anthropology ed. David Bidney, 1963 p. 6)

Thus did David Bidney valiantly launch the investigation into freedom by anthropologists only to immediately then admit: “I realize that hard-headed, realistic anthropologists, including some of the participants in this symposium, would not find themselves in agreement with this anthropologic dream. There is danger, they will protest, that you are reifying Freedom into an absolute entity, just as culture once was. Freedom they will object is a non-scientific, political slogan which betrays its ethnocentric, Western and American origin…”

Freedom, as concept, still evokes this suspicion. That it is “nothing more” than a political slogan; or that it masks the reality of domination, oppression, slavery and power. As well it should given how promiscuously it is exploited.Or, as Edmund Leach so characteristically puts it in his contribution to the same volume: “To prate of Freedom as if it were a separable virtue is the luxurious pursuit of aristocrats and of the more comfortable members of modern affluent society. It has been so since the beginning.” (77)

What Leach expresses here, in part, is the descriptivist bias of anthropology of the time, and specifically of political anthropology: that the goal is comparative analysis without a priori reference to any normative political ideals. This, I think probably resonates with most anthropologists, who would be much less likely to be interested in Freedom as a concept that delimits a certain relationship between action and governance, more more likely to see it as a slogan that has been used as a warrant in colonial, imperial and global economic endeavors; as a tool used to transform existing arrangements in its own name (and secretly in the interests of a global elite). At a first cut this is undeniably so if one simply listens to the way the word is used in the news, and by politicians especially.

Indeed, it is my probably hasty opinion that the whole of “political anthropology” (at least in it’s 1930s-1970s form) shares this bias, despite the fact that it would seem to be this domain to which one would immediately turn for help in understanding the variations in the nature of Freedom. Instead, freedom is excluded from investigation insofar as it contaminates, confuses or otherwise confounds the exploration of objective political structures. Continue reading