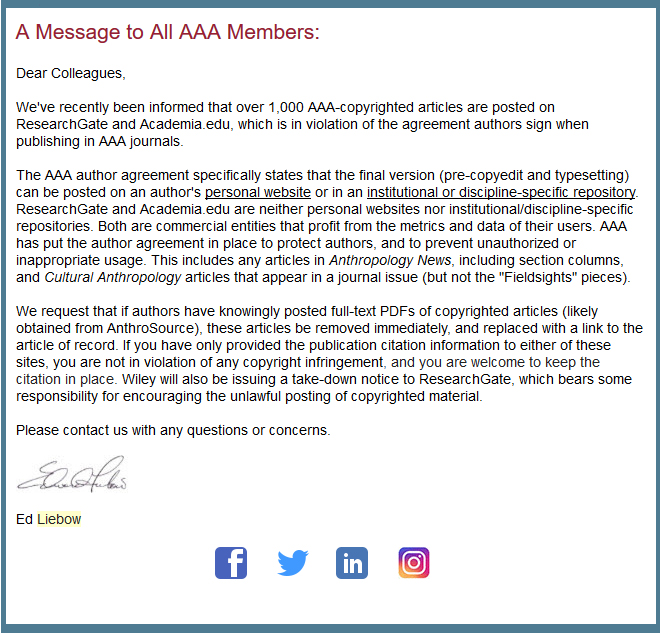

Here we go again. If you’re a member of the American Anthropological Association, you should have received an email this past week (10/17) about avoiding copyright infringement. The message was concise and right to the point: A bunch of members are in violation of their author agreements, and the AAA wants you to take your papers down. Here’s the message in case you missed it:

Basically, the AAA is saying that that more than 1,000 AAA copyrighted articles are in violation of copyright because they have been posted on ResearchGate and Academia.edu. This news is not super shocking, since many of us who publish aren’t particularly informed about the author agreements we sign, let alone how the publishing process works. We just sign those agreements in the rush to publish before we perish…and then sometimes post stuff on commercial sites to make our content “accessible” to the world. Awesome, right? Not so much. This is ultimately to our own detriment.

To quote the Library Loon (as I have before on this site), “The great mass of those who publish in the scholarly literature are pig-ignorant about how scholarly publishing works.” Ouch. But it’s pretty true. How many of you pay close attention to the author agreements you sign? If you did, we might not be having this conversation. Why, you ask? Because you likely signed away your rights, willingly. So when Wiley (or Elsevier, etc) demands that you take your paper down from Academia.edu, they’re just exercising the power you handed to them. As Rex once wrote here on Savage Minds, “if most people realized the way they had signed away their rights to publishers, the open access movement would double or triple in size overnight.”*

Well, this latest message from the AAA is a case in point. So we have all of these AAA members publishing. They’re at various stages of their careers, from stressed our graduate students and junior faculty all the way to stressed out tenured faculty. Everyone is stressed out, and trying to publish and keep their heads above water. Meanwhile, corporate publishers are making a tidy profit, we all write and do peer review for free, and our scholarly work gets closed behind paywalls. Awesome.

Understandably, many people are not happy about the current state of publishing (and access)…so they post copies of their articles on sites like ResearchGate and Academia.edu. But, as it turns out, those sites are there to make money off of the very users who think they’re somehow sticking it to “The Man” by posting it on sites like Academia.edu. Nope. You’re effectively just handing your work–and breaking an agreement you signed–right to another commercial entity that’s looking to make a profit off of you. But these commercial repositories don’t care about your work per se. They likely care much more about monetizing your data (for more, read Chris Kelty’s 2016 post “It’s the Data, Stupid“).

The moral of the story is that we’re not doing anything to change or challenge “the system” when we: 1) sign away our rights to corporate publishers; and then 2) willingly allow our ideas and data to be monetized by other corporations in the name of pseudo-open access. What a mess. Barbara Fister outlined the primary problem a few years back:

All these years librarians have been saying to scholars, “uh, you realize what happens when you sign away your rights, don’t you? You just gave your copyright to a corporation. We have pay them to get access to that content, and anyone who can’t pay can’t read it. Is this really what you had in mind when you wrote up that research?”

Who benefits from our collective ignorance (and inaction), you ask? As the Library Loon explains, “In general, toll-access publishers benefit most from the pig-ignorantly entitled, since such folk are easily manipulated into signing contracts they shouldn’t and vehemently defending organizations and processes out to exploit them.” There you have it. And willingly handing your work over to Academia.edu isn’t changing a thing. As Jason B. Jackson has argued, “Self-piracy is wrong and it is not helping build a better scholarly communication system.” There are other options (Hint: For some shorter-term solutions, look into the ways you can modify your author agreements). Regardless, the real long-term answer lies with developing and maintaining an effective, accessible, and reliable Open Access infrastructure.

So resorting to “self-piracy” by posting your work on Academia.edu or ResearchGate isn’t going to lead to that Open Access Revolution we’re all waiting for. Now what? Well, there are some issues we can deal with now, even while we (hopefully) starting thinking about the future of our scholarly publishing. This brings us back to that email from the AAA, which states:

The AAA author agreement specifically states that the final version (pre-copyedit and typesetting) can be posted on an author’s personal website or in an institutional or discipline-specific repository. ResearchGate and Academia.edu are neither personal websites nor institutional/discipline-speci

fic repositories.

This statement tells us what we can do with our work according to the AAA author agreement. First of all, it’s important to know the terms being used here. The “final version” of a manuscript is the one that a journal accepts (before copy-editing and typesetting). This is different from the “pre-print,” which is the version that you first submit, before review and revision (h/t to Dan Hirschman for the concise terms). So the AAA agreement allows us to post the “final version” on a personal website or an institutional or discipline-specific repository. The first part is pretty straightforward. You can create a website and post your work there, no problem (except it may be hard to find). But the second part gets a little tricky. What’s an “institutional” or “discipline-specific” repository, and where you can find one that the AAA accepts? Do you know where to look?

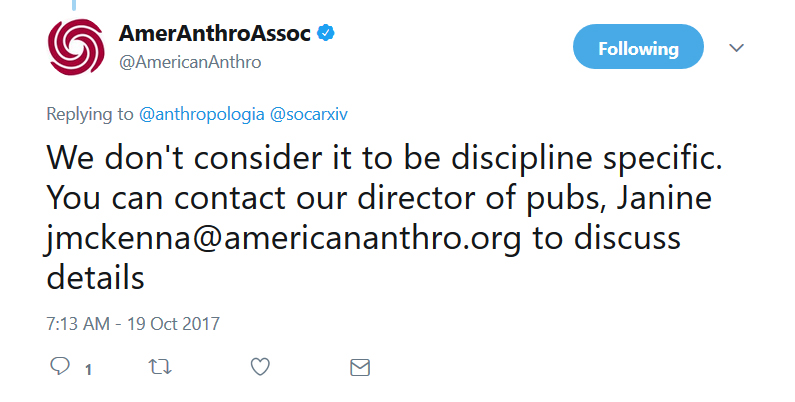

One possibility, you’d think, would be something like SocArXiv (for more about SoxArXiv, check this post). In brief, SocArXiv is a green open access digital repository for social science that runs on the Open Science Framework. I sent a message to the folks at the AAA, asking if they consider SocArXiv to be “discipline-specific.” Here was their reply:

I followed up and asked what discipline-specific repositories they do recommend, but the AAA did not reply. I also sent an email. No reply yet, but I’ll keep you posted. So here’s the thing. The AAA is well-within its rights to issue this notice to members and ask them to take AAA copyrighted material down from ResearchGate and Academia dot edu. But that doesn’t really solve anything. Now might be a good time to investigate why so many people are posting their material on these sites. What is it about these sites–as compared to AnthroSource, for example–that draws so many people to them? But beyond all of that, if the AAA publishing agreement states that authors have a right to post their work in certain repositories, why not clarify which ones are acceptable? Why all the mystery?

I’d also like to know why, specifically, SocArXiv is not an acceptable repository. That appears to be the message from the AAA, but this doesn’t make much sense to me. SocArXiv is non-profit, so I’m not sure why it’s not an option. The current AAA publishing agreement does make room for Green Open Access options, but it’s pretty clear that this is not taking place (considering all that self-piracy out there). Why not? Part of me wonders if this is because some of the terms in our agreements (vague references to personal websites and various repositories) haven’t actually been clearly-defined in practice. If we can’t point specifically to acceptable resources, then how can we expect anyone to use them? A little clarity could go a long way here.

There’s one last point I’d like to make here, and it’s about this line in the message: “AAA has put the author agreement in place to protect authors, and to prevent unauthorized or inappropriate usage.” I’m not quite sure how the AAA is arguing that the agreement works to “protect authors” in any way, and I’d rather not see the message conflated in this fashion. Let’s keep things straight here: This email is about asserting and upholding the publishing agreement that the AAA has with Wiley. That’s fine. We signed away those rights, so we have to pay the proverbial piper. If the primary concern was about protecting authors, not to mention our academic commons, then we’d have a dramatically different publishing agreement…and disciplinary culture of publishing altogether. Just sayin.

*For more check this post from 2015: Forget the outrage: Stop signing away your author rights to corporations. See also Rex’s 2013 post: Don’t blame Elsevier for exercising the rights you gave them.

Yes, we signed off the rights. However, academia.edu ResearchGate, library genesis, or sci-hub, are proof that these contracts and copyright laws are unsustainable. By the share scale of of all types of copyright infringement, which is not only happening in academia, at which point should the rule of desuetude apply? Or, at which point are we going to formalise what is already happening and organise against big publishing corporations (as it is already happening, for example in Germany where Elsevier is being boycotted)? I would hope for the big anthropological associations to be on the people’s side of this fight. In a sense, academia.edu or sci-hub are in a sense the only rescue for academics and students who work at universities that don’t have the money to pay for access, which I believe might be the case with the majority of universities on this planet – could we thus see such acts of disobedience towards the signed contracts as resistance against academic capitalistic colonialism of knowledge?

As for the reasons of so many active users on these portals, I don’t believe that such big masses are unaware of the types of contracts they sign. It might rather be the case that people know but don’t care and plan to breach the contract anyway before even signing it. Most of the top journals which offer the best ‘brownie points’ are not open access, thus uploading the papers on academia is a way to have the cake and eat it. It is also important to note that a bulk of the articles on these portals comes from open-access journals as well. Maybe it just emphasises the need of such author-oriented academic resources. The question then would be – do such portal advance academic endeavours or do they promote nepotism and evaluating research based on the number of clicks rather than merit?

Thanks for this note, Ryan. I wanted to propose at least one answer to your question: “Now might be a good time to investigate why so many people are posting their material on these sites.” While I take it that this is a largely rhetorical question, I’ll take the bait and say that I think the answer that I and many of my colleagues would offer is that we believe that a site such as academic.edu offers people interested in our work one-stop shopping for most of what we have written (not just published work — I have copies of conference presentations, lectures, and other unpublished works on my academic.edu page…). That promotes our work effectively, without forcing a reader to hunt down references in bibliographies. And AnthroSource only includes AAA publications, while with academic.edu I can include publications from many other journals, chapters from edited volumes, etc. Of course, I would never violate a publisher’s copyright 😉

Perhaps there is a generational thing going on here, but having spent nearly 50 years publishing within the traditional system in which publishers profit on my writing, I accept this as the way things work, and while I am very happy to see alternative forms of disseminating our work being explored, I wonder if the high dudgeon over academia.edu also profiting from my work is fully justified? After all, I can use academia.edu at no cost to myself, while journal subscriptions are prohibitively expensive these days. If you want more services from academia.edu you can pay for those, but that’s your choice, and I wouldn’t lump it with Elsevier for that reason.

This post smacks a little of victim-blaming to me. It is not really the case that the individual would-be self-pirate has a lot of choice about whether to sign their rights over to Wiley et al. in the first place. Rather, one might be excused to think that AAA is exactly the organization that should be at the forefront of providing its members with access to open access repositories and publication venues.

Perhaps section websites are “discipline specific repositories?” SACC, for example, publishes papers online and open access.

Brilliantly written Ryan. Sadly, the issues you articulate here are just the beginning of a litany of problems with the current state of scholarly publishing. In addition to handsome sums made by corporate publishers (an NPR piece some years back claimed that the scholarship publishing industry has one of the highest profit margins in the world) that you rightly point out, we also know it’s an incredibly capricious industry that can often feel like an old boys’ network – the eager networkers typically have an easier time publishing than the quiet tinkerers. This suggests that the industry is also very much an insider’s game, where who you know is often more valuable than what you know. And in the process we research, write, and edit all for free so we can add a line to our CVs. I’m always astounded by the irony of so many Marxists participating in this racket.

I think Barbara makes a very good point about Academia and ResearchGate. Yes, these are for profit companies but they don’t make any direct profits off of us as readers or users unless we subscribe to premium content. Also, their readership metrics are very good with an incredibly wide reach. If AAA wants to take this serious they need to introduce their own platform with as much readership as Academia, and sorry but SocArXiv just doesn’t have the same reach as Academia either. I can appreciate what this platform is doing but posting there just doesn’t have the same wide reach. At this point as a membership based organization meant to promote and encourage scholarship, AAA is doing a horrible job of only caring about Wiley’s bottom line rather than its own members’ research and productivity.

While not a fan myself of Academia.edu, one can use it while also making (much sounder for the long haul) use of a institutional or disciplinary repository. I confirmed this just now with a paper of my own, adding the Academia.edu equested article metadata to my account there and linking to the associated paper in my university’s Institutional Repository without uploading the paper to Academia.edu. In this way, someone looking for me or my topics on that site (Academia.edu) can find it, but the paper lives (where it ideally should) on a durable, well-maintained institutional repository, where it will be preserved, moved to new file formats, etc. for decades to come, in the public interest. While an sound institutional repository would be best, the same approach can be used with a personal website or an subject repository. In this way, the Academia.edu fans can be compliant with their unmodified AAA author agreements, enjoy the things they like (or most of them) about Academia.edu, and do the right thing for the scholarly record and its wide availability.

W.r.t. the “protect authors” bit: I just happened to have written a post on publisher-speak, and also addressed the commonly encountered spin that what they’re doing somehow benefits authors. It sounds incredulous every time, but from their perspective, my guess is that they consider themselves to be essential to the authors (which is somewhat true at the moment – which is why we want the system to change), and thus protecting themselves from cancelled subscriptions would indirectly protect the authors.

“What is it about these sites–as compared to AnthroSource, for example–that draws so many people to them?”

User-friendly. I have an institutional site, but uploading a PDF requires 15 minutes to remember how to do it, and then a bunch of clickings and approvings. Academia is simple and elegant. It must be hard/expensive to design a beautiful and user-friendly site, because the non-commercial ones are so rarely so.

Linked. The institutional site is awkward and has a strange URL, and comes and goes, and nobody can find it (although it’s better on the search engines these days). In contrast, the commercial sites are linked to colleagues and to friends in others departments. I follow them, I get regular updates, I can see how many people are reading mine, I get messages from them, etc. It’s like Facebook for academics.

Thanks for the great post.

So the AAA is bad at communicating (e.g. about what counts as a discipline-specific archive); it’s bad at representing its end users’ interests; and it’s willing to make blatantly implausible, disingenuous statements in hopes of persuading its users to misrecognize their own interests as being equivalent to the AAA’s corporate interests (and those of Wiley).

To me, this is more than about publishing. This is about a slow motion crisis in the AAA’s long term credibility as a representative of the very people it is supposed to represent.

Ryan’s thoughtful piece deserves serious discussion. On reading it, my first thought was: yes, the coin of Caesar. In submitting (do not miss the connotations of that word!) a paper to a journal, the anthropologist-writer sets in motion a chain of events that adds to its value if and when it is published. An editor (who may or not be paid) spends time on it; several peer reviewers likewise (though these are unpaid drudges – wretches like the author herself); a proofreader, copy editor, and typesetter (who are paid) devote hours to it. Then there are the costs of publication and distribution. In return for that work and expense, the author signs away the right to have the paper appear in other venues. Fair is fair.

However, my second thought on reading the AAA notice (not being a member of that august organization, I hadn’t seen it before), brought to mind John Steinbeck’s remark on his 1963 visit to the Berlin Wall, to the effect that the beast, sensing its coming extinction, begins to grow scales. Scales, here pay walls. Viewed from that perspective, how precious and arrogant the AAA takedown notice appears. With a membership of ten or twelve thousand (I couldn’t find an exact number, perhaps someone better acquainted with the beast can supply that) and an impact factor scraping the bottom at around 1.6, what, really, does the AAA have to protect?

It’s a sorry state of affairs, both for those excluded and for those lucky (?) few whose shot at tenure is enhanced while meaningful discussion of their work is reduced to a trickle, if that.

I see only two ways out of this dilemma. One: Before an editor got hold of your paper and sent it out to strangers to piss in the pot, the paper was yours, your own unique creation. Surely you are free to post that wherever you like, and you just might find others interested enough to exchange ideas. Two: The possibility of substantive online discussion of anthropological works is remote. I know of only one site (though there may be others): Open Anthropology Cooperative, where open access is truly open (you’re free to post, free to comment at length). In the current oppressive atmosphere of pay walls, perhaps worth checking out.

The obvious solution for this is for the AAA to create a “discipline specific” repository where members might deposit their papers. Obviously the takedown notice indicates that some at AAA are committed to copyright enforcement (or feel legally compelled by the agreement with Wiley to perform such commitment), but perhaps it is possible for the members to at least vote their endorsement for such a repository at the upcoming business meeting? I see that the deadline for submitting motions for the agenda is November 1. The main difficulty I see is that submitting such a motion requires estimating the cost to the AAA of adopting it. Myself, I have not idea what even the technical aspects of setting up and maintaining such a website might be, but perhaps someone is more knowledgeable than I?

Agreed btw that there is little point in criticizing individuals for working as best they can in the circumstances they find themselves either by signing agreements that are the condition for publishing in some of the main places where others might see their work, or posting it on services that are, whatever their business model, currently free for those who simply want to post their own work or see other people’s work.

Daniel Rosenblatt posts an important suggestion that reflects the very steps AAA is taking. The AAA Executive Board considered just such a proposal and voted in May to establish this kind of anthropology repository. In order to ensure that it is a fully functioning, easy-to-use resource for the discipline, AAA is currently in the process of gathering information (including on costs, functionality and potential providers). AAA’s member-based committees are also involved in this process and the discussion on how to build such a repository. AAA is a community and the publishing program is a collective effort, so the functions need to meet the needs of all of anthropology’s subdisciplines.

The EB also voted in May for the Publishing Futures Committee to review the author agreement and address how to make the agreement best meet the needs of the field. To get a sense of the broader scope of the AAA publishing program, please see my recent blog post: The AAA Publishing Portfolio Principle.” https://blog.americananthro.org/2017/10/24/the-aaa-publishing-portfolio-principle-the-rights-of-the-individual/

A contrarian view. The last thing anthropologists need is a discipline-specific repository. What the world needs now is more of the kind of cross-discipline collaboration that makes papers readable and citable outside a specific discipline. Anthropologists pulling themselves and their writing into what will be, in effect, a disciplinary black hole makes no sense at all.

Just to reiterate what Jason Jackson said, using ResearchGate or Academia does not preclude one from also using an institutional repository. In fact, using an IR is one of the most important steps a writer can take after publication. And though John Schaefer laments the clunkiness of his institution’s IR (some are better than others tbh), they really are quite beneficial because (1) they promote digital preservation — neither ResearchGate nor Academia care about the longevity of your bitstream; and (2) they append essential metadata that helps your work get discovered, which is the whole point of using these third party platforms. So wherever you stand on the AAA’s author agreement etc, please please please use your IR.

And as Ryan and others have pointed out, its really weird that the AAA has decided that SocArXiv is not a disciplinary repository. But just as arbitrary is the definition of ResearchGate and Academia as something other than a personal website. What is a website? What makes one personal?

Are RG and Academia barred from this set because a third party runs the software and servers? This is like saying that if I bake a cake from a Betty Crocker box mix that its not my cake, but Betty Crocker’s! Savage Minds runs WordPress and sits on a third party’s servers, we consider it ours because we create the content even though the bits sit on a private company’s servers. Likewise, as scholars we write our papers in MS Word but they are our papers not Microsofts. Similarly it should be the case the when users create content on RG and Academia that those webpages belong to them.

In exploring all their options, OA advocates in the AAA might also choose the challenge this arbitrary definition of “personal website”.