I recently applied for “academic promotion” from Assistant to Associate Professor. I’m still awaiting the results, but I wanted to share part of that process with you: the ubiquitous “statement of teaching philosophy.” As this is something many people also struggle with in job applications, I thought I’d talk a little about the genre and share my own statement in full. Sharing my statement takes a little guts, as I really struggled to write an honest statement as opposed to the kind of jargon and cliché ridden statements I’ve seen when sitting on the other side of a job search committee, or when looking for sample documents on the web. (Rex sent me this page on writing such documents and the “Rubric for Statements of Teaching Philosophy” included there is one of the few genuinely helpful documents I found.)

Why is this statement so hard to write? Well, for one thing, I think it makes us painfully aware of the gap between our teaching ideals and our actual classroom practices. We can talk all we want about various teaching philosophies, but much of what most teachers do in the classroom is essentially the same. Even Mike Wesch, who wrote here about his theory of anti-teaching, has more recently written about “why good classes fail“:

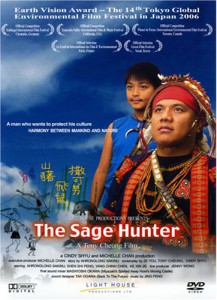

In fact, the few truly fantastic classes I have stumbled into were just as likely to be “sage on the stage” lectures as they were to be based on more participatory methods. And the disheartening reality has been that a really bad lecture doesn’t fail as badly as a really poorly executed participatory class. Many of these professors seem to do everything “right.” They ask their students questions, pause and let them discuss with their neighbors, show YouTube videos that relate to their own experience, and invite discussion. But disinterest and disengagement still reign. Why?

I appreciate Wesch’s thoughts on this, and I strongly recommend reading the whole piece. (And look forward to his forthcoming book on teaching.) There is also an article about his re-think in the Chronicle. I mention it because it gives me comfort in the more modest approach I’ve taken in my own statement of teaching philosophy. I talk, for instance, about making my goals explicit. This may not seem like much, but in practice I’ve found that it is very difficult to do well and also very helpful to students when done properly. It isn’t the kind of thing that gets one written up in the Chronicle, but it is something I’ve thought long and hard about. It isn’t just about writing a good syllabus, but about spending time in class teaching one’s expectations and the reasons behind them. (In my case we actually created a whole new course to accomplish this goal.)

I hope my document is useful for others working on articulating their own teaching philosophy. I also think it highlights some of the unique challenges I face teaching here in Taiwan and might be interesting even for those not planning on writing such a statement anytime soon.

Continue reading →