[Savage Minds is pleased to publish this essay by Ruth Behar as part of our Writers’ Workshop series. Ruth is the Victor Haim Perera Collegiate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Michigan. She is the author of numerous articles and books including Translated Woman: Crossing the Border With Esperanza’s Story (Beacon Press, 1993), The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart (Beacon Press, 1996), An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba (Rutgers University Press, 2007), Traveling Heavy: A Memoir In Between Journeys (Duke University Press, 2013), and is co-editor with Deborah Gordon of Women Writing Culture (University of California Press, 1995).]

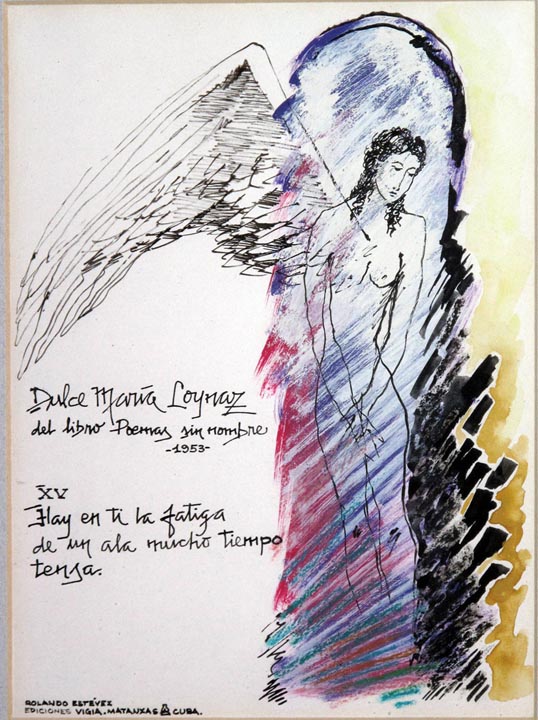

Years ago, when I started returning to Havana, the city where I was born, I had the good fortune to be welcomed into the home of Cuban poet, Dulce María Loynaz. By then she was in her nineties, frail as a sparrow, nearly blind, and at death’s doorstep, but enormously lucid.

Inspired by her meditative Poemas sin nombre (Poems With No Name), I had written a few poems of my own, and Dulce María had the largeness of heart to ask me to read them aloud to her in the grand salon of her dilapidated mansion. She nodded kindly after each poem and when I finished I thought to ask her, “What advice would you give a writer?” Continue reading