Recently, I enrolled in two multi-day training workshops in the United Kingdom with the pretense of gathering ethnographic data about emergent cultures of practice surrounding new technologies. The first was an ethical hacking workshop in Manchester–where we learned how to “ethically” use malware to examine, test, and ultimately penetrate and control computer servers. The second was a class to acquire a certificate to be able to conduct commercial drone flights. These experiences revealed interesting insights into the process of professionalisation as well as contemporary ethnographic methodologies. I will briefly theorise the process of professionalisation, how this happens, why it is interesting, and why training-as-ethnography is an important place to participate in this process.

Tag Archives: digital media

Analogue to Digital and Back Again, Part II

By Kathryn Killackey (Killackey Illustration and Design)

This post is part of this month’s analog/digital series and the second post discussing my work as an archaeological illustrator in relation to analogue and digital media. In the previous post I outlined my mostly analogue workflow with some digital skeuomorphs and explored the differences between illustration and 3D modeling. Here I’d like to share some ways I’ve recently expanded my use of the digital in my workflow and explored a constructive interplay between the digital and analogue.

I am the site illustrator for Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic archaeological site in Turkey. I started working there in 1999 as an archaeobotanist, and since 2007 I’ve been the project’s illustrator. Every summer I spend about two months drawing artifacts and recording on-site features. Over the years I’ve seen the project transition from entirely analogue recording to a mix of digital and analogue, until it has become almost entirely digital in some trenches. At this point the project employs tablets, laser scanners, and even drones. Dr. Maurizio Forte’s team from Duke University and Dr. Nicoló Dell’Unto from Lund University have spent the last several years testing these digital technologies on site. Until recently my work has mostly been unaffected by this transition to digital, I’ve carried on with my analogue workflow on a parallel track (see my earlier post for some advantages to analogue media in illustration). But over the last couple years several situations have arisen where I have had to re-evaluate my approach and consider integrating some of these new digital methods.

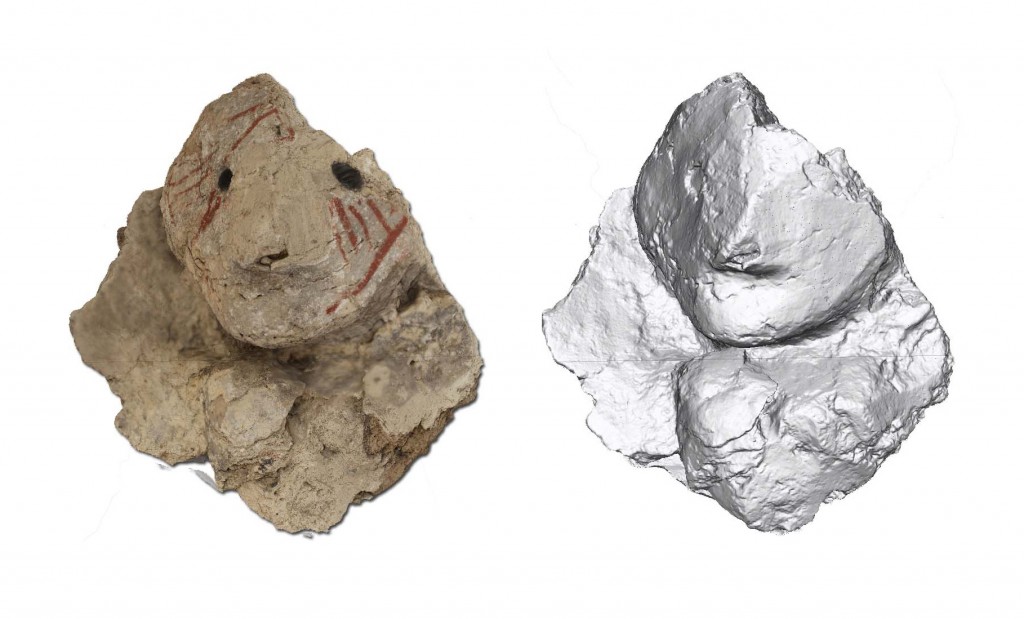

For example, this past summer I was tasked with illustrating a large, fragile lump of molded plaster in the shape of a head with painted ochre designs. I sat in front of the head with all my drawing tools laid out, picked up my pencil, and stopped. The plaster feature had already been 3D modeled by Dr. Dell’Unto and photographed by site photographer Jason Quinlan from every angle. What was my analogue pencil and paper drawing going to record that these other digital methods hadn’t already? Why illustrate?

Mixed Exhibits: The best of both worlds?

Post by Laia Pujol-Tost:

Archaeology is mostly about materiality. Its epistemological foundation is based on the relationship between humans and the material culture. Some of this objects, will later be displayed in museums to convey interpretations of the past. Yet, as Yannis Hamilakis and other authors have argued, Archaeology is a modern “science”. As such, it is mostly about the eye, and little about the body. On site, it mostly records and analyses visual, spatial, geometrical features. At the museum, this has meant a universal rule of not touching, and objects are isolated in showcases, for the sake of… mutual protection.

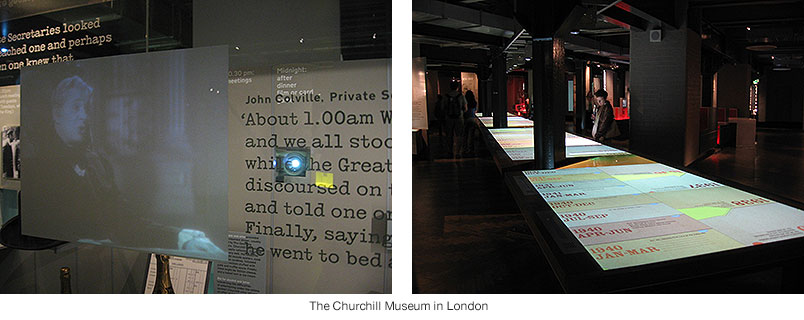

Then came Information and Communication Technologies (before they were called Digital Media), which under the promise of increased accessibility, interaction and engagement, reduced archaeological heritage even more to image and visualization: it had been digitalized; that is, de-materialized and even “de-musealized”. A series of evaluations conducted in museums since the 90s evidenced a conflict between the exhibition and the new media. The main reason being, as Christian Heath and Dirk vom Lehn pointed out, that exhibitions and computers belonged to different communication paradigms.

Around that time, several studies conducted in different European museums led me to the conclusion that the best way to integrate digital technologies was to stop just placing computers in exhibitions, and instead re-design the interfaces purposefully for such environments. Yet, what happened was the advent of mobile devices.

Meanwhile, some researchers working in the highly interdisciplinary field of Human-Computer Interaction started advocating for more natural ways to interact with computers. As a result, a new field called Tangible or Embodied Interaction arose around the 1990s. In this context, the concept of “Tangible User Interface” was developed. In TUIs, the interface is not anymore a PC but an (everyday) object. This takes advantage of the human capacity to manipulate objects, and allows a better integration with the context of use. Since the 2000s, labs used occasionally the cultural field as test bed; until 2013, when the first EU-funded project specifically devoted to tangible interactive experiences in Cultural Heritage settings was set up.

Now 3D printing has become the hype. As it happened with computers in the previous century, this technology is not new: it has been used in the engineering field for rapid-prototyping since the 1980s. But only recently it has become accessible to markets. Its applications are manifold: engineering, clothing, food, housing, health… But more than that, its implications regarding traditional product design, production and distribution chains are so enormous, that some people already talk about additive manufacturing being the next industrial revolution. The Cultural Heritage field has not been indifferent to this development. For example, the Smithsonian has started the X3D project, aimed at digitalizing and allowing the 3D printing of its collections. In the academic domain, some sessions at the EAA conference dealt with the implications of 3D printed replicas for Archaeology. Finally, the first mixed exhibits have appeared in European museums the last years, used either as mediators, smart replicas, top tables for shared exploration and gaming, or as full-body interactive environments.

I am so excited about it! Does this mean that we may finally close the circle and, after such a long history of “voyeurism”, fully acknowledge materiality and tangibility in the cultural heritage field? It is interesting to note that, as it happened before with interaction or storytelling, we needed the pressure of the digital revolution to (re)discover or finally accept elements that already existed in the museums field. Still, I believe there is a big potential in this area, more than with digital media, and this is exactly what I am starting to investigate now. On the one hand, the specific advantages of smart replicas or tangible exhibits for Cultural Heritage settings. I have adapted Eva Hornecker’s overview of Tangible Interaction to list the following features:

- Appreciation of the materiality of the real object.

- Direct manipulation instead of just visualization.

- Performative action instead of passive gaze.

- Natural interaction without added symbolism.

- Natural integration in the exhibition environment.

- Non-fragmented visibility.

- Suitability for exploration in group.

- Personalization (especially suitable for children).

On the other hand, I am concerned about the strategies and threats for their adoption in museums. The experience shows that, as costs decrease, the availability and penetration of technologies increase. Still, the problem is designing and maintaining high-tech exhibits. Most museums tend to outsource digital media projects; but this has more often than not proven to be a bittersweet experience in terms of budget, sustainability, end-product, workflow, etc. Institutions are currently implementing different solutions. For example, EU-funded projects emphasize the creation of do-it-yourself authoring tools. Also, the big museums in the USA and Europe give strong support to the creation of their own digital media departments, so that such experiences can be fully developed in-house.

Yet, as we witness again a concern similar to supposed threat posed by the virtual to the brick-and-mortar museum, we first need to complete the unfinished debate around the concept of authenticity in cultural heritage. In my opinion, the problem to be solved is not with smart replicas (which, following Bernard Deloche’s taxonomy, only act as analogical or analytical substitutes), but with the role of originals in the age of information, commodification, and globalization. However, this is a discussion for another time and place.

(Part of this month’s Analog/Digital series, thanks to Savage Minds for hosting!)

A Tempest in a Digital Teapot

It was hot, but that was not unusual. We woke up at the first call to prayer to be on site at sunrise. I would trudge through the dimly-lit streets of the village, up to the ancient tell, and sit next to my trench until I had enough light to see my paperwork. The cut limestone went from dull gray, to a rosy pink, then that brief and magical moment called the golden hour, when the archaeology would become clear and beautifully lit and I would rush around trying to take the important photos of the day. Then the light would become hard, white-hot, and often over 100F. By lunchtime all of the crisp angles of the limestone would disappear into a smeary haze, hardly worth bothering with a camera. Photographs of people were impossible too—everyone was dusty, hot, irritable, half in shadow under hats, scarves.

I picked up my camera and climbed out of the Mamluk building I was excavating, on my way down the ancient tell of Dhiban and back up the neighboring tell of the modern town of Dhiban. As I walked between the Byzantine, Roman, Nabatean and Islamic piles of cut stone, a faint trace of smoke made me hesitate, then come off the winding goat path. Two of the Bani Hamida bedouin who worked with us on site were stoking a small fire on the tell. While making fires on the archaeology was certainly not encouraged, the local community had been using the tell to socialize for a long time. I greeted the men and they invited me to sit and have qahwa, a strong, hot, sweet, green coffee served in many of the local hospitality rituals and customs. I refused once, then twice, then looked over my shoulder at the vanishing backs of my fellow archaeologists, on their way to breakfast. Then I accepted a cup. But first, I pulled out my camera and snapped a photo.

Pixel vs Pigment. The goal of Virtual Reality in Archaeology

Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Colleen Morgan.

Post by Laia Pujol-Tost.

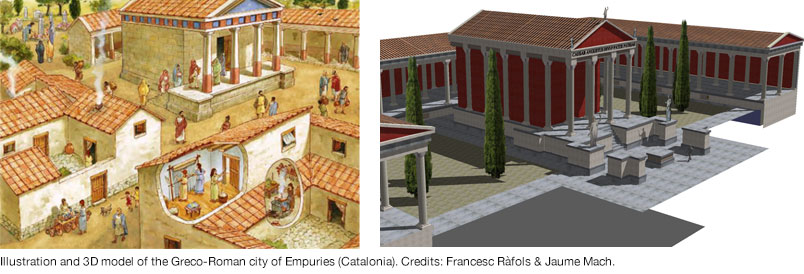

Archaeology has a long tradition of using visual representations to depict the past. For most of its history, images were done by hand and based on artistic skills and conventions. But the last fifteen years, we have witnessed 3D models take over archaeological visualization. It is interesting to note that while hand-drawn depictions tend to show human figures and seem to be associated with scenes of “daily life”, virtual reconstructions mostly show architectural remains and public spaces, usually devoid of people and objects. Yet, authors state that their intention is to represent the past.

My field of research is what we now call Virtual Archaeology, but I started investigating when we still talked about “VR applications in Archaeology”. I have seen it become mainstream and evolve; and I wonder why after almost twenty years of technological improvements and theoretical debate, virtual reconstructions are still empty. Especially in comparison with drawings. Do the virtual and the physical have implicitly different goals? Are they subject to different perceptions or expectations by researchers and/or audiences? Have they received different historical influences? Maybe technological capacities still play a role?

Mobile apps and the material world

[Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Sara Perry.]

This is the first in a series of posts, coordinated with Colleen Morgan, on the relations between analog and digital cultures. Over the next month, through the contributions of a variety of archaeologists, we will explore the concept of materiality in an age where the nature of ‘the material’ is rapidly shifting. How do physical materials and digital materials shape one another? How does experimentation with the digital rethink the dimensions of the analog, and vice versa? How, if at all, do we distinguish between one and the other – and is this even necessary (or possible) today? How have our understandings of ‘the real’ – of ‘things’ and ‘facts’ – of presence and the body – of aura and authenticity – been shifted by interactions between physical and digital materials?

As the premiere scholars of materiality, archaeologists are well-versed in the continuities between, and changes to, artifacts. Here, we probe their boundaries through discussion of our engagements at the intersections of the analog and the digital. I begin with some critical comments on mobile apps: oft enrolled in visitor experiences at archaeology and heritage sites, are these digital tools actually valuable?

The Privacy Paradox: IRBs in an Era of NSA Mass Surveillance

[This invited post was written by Daniel O’Maley, who recently graduated with a PhD in cultural anthropology from Vanderbilt University. His research focuses on the global Internet freedom movement and the link between digital technology and new forms of democratic participation. You can read more about him and his research here]

Increasingly, our lives are mediated by the Internet and other digital technologies. For anthropologists like myself, this presents new opportunities for research, but the digitization, exchange, and storage of personal data also generate new privacy concerns for our participants. During my research on Brazilian Internet freedom activists, I learned about both the potentials of the Internet, as well as the way that digital technology can, and is, being abused to violate civil liberties. What I call the “privacy paradox,” refers to the situation in which the U.S. government at once defends research participants’ privacy through Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) while it simultaneously violates their privacy on a massive, global scale through mass surveillance national security apparatus.

The privacy paradox become apparent to me in July 2013, just a month after the Snowden leaks that exposed NSA mass surveillance, when I sat down to interview a high-level official of a Brazilian IT firm. Before the interview, I detailed the measures I was taking to ensure that his personal data would be protected and I explained that this was required by Vanderbilt’s IRB per U.S. law. Upon hearing this, the IT official looked at me incredulously. Over the previous two months the front pages of newspapers had been plastered with articles detailing U.S. government surveillance projects with codenames like PRISM, XKeyscore, and Stellar Wind that used the global telecommunications infrastructure to collect personal data on people around the world. My interviewee was well-versed in issues of privacy in the digital age, so to hear me state that the U.S. government was concerned with his privacy was laughable.

Ethics, Visual Media and the Digital

As c.10,000 anthropologists descend upon Washington, D.C. this week for the annual American Anthropological Association conference, my colleague Jonathan Marion (University of Arkansas) and I, alongside an international cadre of researchers, have joined a long-standing conversation about the relationship between digital cultures, visual media and ethics that will fully manifest on Saturday, but that exists online in multiple forms too (more below). That conversation is a complicated one, known to induce frustration, confusion, feelings of helplessness, despondency and, at times, defiance among those who engage in it. By this I refer to the business of negotiating (1) the ethical implications of our own research programmes, (2) the experience of formal ethical review, and (3) ethical issues borne out of the everyday actions of our communities of study. Such ‘business’ is seemingly made even more complicated when digital and visual media are brought into the fold.

Indeed, more than ten years ago Gross, Katz and Ruby published Image Ethics in the Digital Age, a pioneering volume whose topical concerns – privacy, authenticity, control, access and exposure – are arguably more conspicuous now than in 2003. Today, their complexities appear to be extending as digital interactions themselves extend, and the consequence is an inevitably fraught landscape of practice with debatable outcomes.

What archaeologists do: Research Design and the Media Archaeology Drive Project (MAD-P)

For the past two weeks, Colleen Morgan and I have been outlining the background to an actual “media archaeology” project wherein we extend the intellectual and methodological toolkit of archaeology into the study of media objects (especially, digital media objects). The impetus for this project is outlined here, and the theoretical context here. Having set up the framework, we delve now into our actual research programme, which we affectionately refer to as MAD-P: the Media Archaeology Drive Project.

As our aim here is to model good practice, and to benefit from the collective intelligence of Savage Minds, we present below the project research design for constructive critique. In brief, we’ve excavated a found hard drive, and while in the next post we’ll document for you our process, our written and photographic records (stay tuned for a Harris Matrix), and our interpretative outputs, here we detail the nature of our field site and field method, ethical engagement with our excavation, and sustainability/access to our data.

Colleen is the principle author of this research design, and it’s important for me to say that I’ve learned much through my collaboration with her. As someone who has spent the past 10 years outside of the excavation trench, it was very meaningful for me to jump back in—using single context recording no less!—with Colleen as my guide. Here is the project whose results you’ll see reported over the next week on Savage Minds… Continue reading

What archaeologists do

[Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Sara Perry.]

On Friday my colleague, Dr Colleen Morgan, and I will be co-delivering a paper at the University of Bradford’s Archaeologies of Media and Film conference in Bradford, UK. For anyone not familiar with the still-emerging field of “media archaeology,” this is an exciting event, featuring some of its pivotal thinkers (e.g. Jussi Parikka, Thomas Elsaesser), and a diversity of researchers discussing everything from 19th century stereoscopy to statistical diagrams and animated GIFs. As the organisers stated in their Call for Papers, the conference is a gathering of various interests, all converging on “an approach that examines or reconsiders historical media in order to illuminate, disrupt and challenge our understanding of the present and future.”

Colleen and I are talking on the last day, in the last block of parallel sessions, in a line-up of speakers who appear to be the only other archaeologists at the event. While I’ll delve into the details of “media archaeology” in a subsequent post, it is notable that archaeologists effectively never feature in this stream of enquiry. Rarely do archaeologists or heritage specialists attempt to overtly insert themselves into the media archaeological discourse (Pogacar 2014 is arguably one exception), and neither do media archaeologists typically reach out to archaeology for intellectual or methodological contributions (but see Mattern 2012, 2013; Nesselroth-Woyzbun 2013). Indeed, the media archaeological literature has explicitly distanced itself from archaeology, with the editors of one keystone volume writing:

“Media archaeology should not be confused with archaeology as a discipline. When media archaeologists claim that they are ‘excavating’ media—cultural phenomena, the word should be understood in a specific way. Industrial archaeology, for example, digs through the foundations of demolished factories, boarding-houses, and dumps, revealing clues about habits, lifestyles, economic and social stratifications, and possibly deadly diseases. Media archaeology rummages textual, visual, and auditory archives as well as collections of artifacts, emphasizing both the discursive and the material manifestations of culture. Its explorations move fluidly between disciplines…” (Huhtamo and Parikka 2011).

I’ve been curious about this trend of archaeology-free media archaeology for a while now, particularly after attending Decoding the Digital last year at the University of Rochester (see Matthew Tyler-Jones’ excellent review of the meeting in two parts: I and II). At this conference, one of the attendees with an obvious media archaeological bent lamented the difficulties of studying abandoned virtual worlds wherein direct identification of human beings was essentially impossible (for all that was left in these worlds were fleeting digital traces). The implication was that few methodologies were available to negotiate this seemingly hopeless interrogative exercise.

So Who Really Did Build the Assemblage which is the Internet? (Part 6)

The internet is translative boundary object for political thought, situated between four liberal ideologies about freedom and the state, corporation, individual, and the public. The internet is thus a parallax object, looking different from what ideological perspective one looks at it. Continue reading

Continue reading

Who Built the Internet? We Did! (Part 5)

In 2006, according to Time Magazine, the theory of technoindividualism “took a serious beating.” In electing You to the position of the Person of the Year, Time prophesized the fourth discourse of internet historiographical revisionism following President Obama’s statement. It was not the state, corporations, or genius insiders who made the internet, nonfiction best seller author and transhuman apologist Steven Johnson claimed in the New York Times, but Us who built the internet. Continue reading

Who Built the Internet? Studly Genius Individuals! (Part 4)

Thus far Crovitz’s and Manjoo’s positions are located within modernist historiographical and liberal conceptions over the battles of freedom, with network technology as a proxy battlefield, and the role of states and corporations as extenders or inhibitors of those freedoms. The third leg of this modernist battle has to be initiated by the sole genius and his impact on the development of the internet. Continue reading

Who Built the Internet? The State! (Part 3)

Despite Crovitz’s best wishes, Taylor’s Xerox PARC Ethernet didn’t become the internet as Slate’s Farhad Manjoo and Time’s Harry McCracken explain. Two days later, Manjoo rebutted Crovitz’s “almost hysterically false” argument. Aligning with given wisdom, Manjoo stated that the internet was financed and created by the US government. Despite being more historically accurate than Crovitz’s argument this statement is also political. In reminding the residents of Roanoke of the government’s role in the founding of the internet, President Obama, according to Manjoo, “argued that wealthy business people owe some of their success to the government’s investment in education and basic infrastructure.” This argument is progressive, social democratic, or socially liberal–advocating for responsible taxation and the shared burden of national identification, and is therefore a political narrative opposed to the Darwinism of technolibertarianism expounded by the Technology Liberation Front. Continue reading

Who Built the Internet? Corporations! (Part 2)

Obama may have gaffed, neoliberal assistant editors at Fox News and the Republican National Committee, exploitatively edited, repurposed, and exaggerated the speech, but it was Wall Street Journal writer L. Gordon Crovitz who mistook the misedits as evidence for US executive branch internet revisionism. Crovitz, ex-publisher of the Journal, ex-executive at Dow Jones, and social media start-up entrepreneur, attacked President Obama’s statement that the internet was funded and engineered by the federal government. “It’s an urban legend that the government launched the Internet,” he idiosyncratically declared. The crux of Crovitz’s argument was focused on Robert Taylor, who ran the ARPAnet, a US DAPRA project that connected computer networks to computer networks. Taylor, according to Crovitz, stated that this proto-internet, “was not an Internet.” And therefore, most importantly for Crovitz, this meant that President Obama was dead wrong, Taylor, a federal employee at this time did not help to invent the internet. The internet was not made by engineers paid by public but private hands. Crovitz’s twist on the accepted story is that Taylor later made a different internet, ethernet, at Xerox PARC where we worked after DARPA. And it was Ethernet that became the internet. Continue reading