When Google engineer James Damore wrote his now-infamous memo about how woman are naturally unsuited to work at Google, anthropologists everywhere groaned inwardly. Our discipline’s lot in life is tragic. After about a century of research, we have a pretty good understanding of how human beings work. And yet, our findings run counter to what the average American’s ideas about how society and culture function. As a result, we face the unenviable task of having to constantly explain, over and over again, generation in and generation out, our truths to a skeptical public. It sucks. It’s tempting to throw up your hands and walk away from discussion. But we have no choice: Our integrity as scholars and scientists demands that we wade in to every public debate about race, gender, and human nature in order to explain — once again — how people actually work.

Tag Archives: Public Anthropology

TAL + SM: The Stories Bones Tell

This Anthro Life – Savage Minds Crossover Series, part 4

This Anthro Life – Savage Minds Crossover Series, part 4

by Adam Gamwell and Ryan Collins

This Anthro Life has teamed up with Savage Minds to bring you a special 5-part podcast and blog crossover series. While thinking together as two anthropological productions that exist for multiple kinds of audiences and publics, we became inspired to have a series of conversations about why anthropology matters today. We’re sitting down with some of the folks behind Savage Minds, SAPIENS, the American Anthropological Association and the Society for American Archaeology to bring you conversations on anthropological thinking and its relevance through an innovative blend of audio and text.

In our fourth episode of the TAL + SM collaboration Ryan and Adam chat with Dr. Kristina Killgrove about her strategies for engaging popular, interdisciplinary audiences through writing. We also explore Kristina’s strategies for choosing content to cover in her blog, Powered by Osteons, and end by considering some ways research has been changing in terms of crowdfunding and open access data.

TAL + SM: Anthropology and Science Journalism, A New Genre?

This Anthro Life – Savage Minds Crossover Series, part 3

by Adam Gamwell and Ryan Collins

This Anthro Life has teamed up with Savage Minds to bring you a special 5-part podcast and blog crossover series. While thinking together as two anthropological productions that exist for multiple kinds of audiences and publics, we became inspired to have a series of conversations about why anthropology matters today. We’re sitting down with some of the folks behind Savage Minds, SAPIENS, the American Anthropological Association and the Society for American Archaeology to bring you conversations on anthropological thinking and its relevance through an innovative blend of audio and text.

In our third episode of the TAL + SM crossover series, we explored SAPIENS’ approach to producing anthropological content for popular audiences. Ryan and Adam were joined by the digital editor of SAPIENS, Daniel Salas, to discuss the implications of using anthropology to engage the public through journalism. The episode focused on the questions How do you reconcile scientific and anthropological writing, and is this mixture a new genre? Is there a balance to be found between producing timeless “evergreen” stories versus current events focused content for audience engagement?

Be sure to check out the first and second episodes of the TAL + SM collaboration: Writing “in my Culture” and Anthropology has Always Been out There. Continue reading

TAL + SM: Anthropology has Always been Out There

This Anthro Life – Savage Minds Crossover Series, part 2

This Anthro Life – Savage Minds Crossover Series, part 2

by Adam Gamwell and Ryan Collins, with Leslie Walker

This Anthro Life has teamed up with Savage Minds to bring you a special 5-part podcast and blog crossover series. While thinking together as two anthropological productions that exist for multiple kinds of audiences and publics, we became inspired to have a series of conversations about why anthropology matters today. For this series we’re sitting down with some of the folks behind Savage Minds, SAPIENS, the American Anthropological Association and the Society for American Archaeology to bring you conversations on anthropological thinking and its relevance through an innovative blend of audio and text. That means each week for the month of June we’ll bring you two dialogues – one podcast and one blog post – with innovative anthropological thinkers and doers.

You can check out the the second episode of the collaboration titled: Anthropology has Always been Out There, here.

Counting and Being Counted: New AAA Tenure and Promotion Guidelines on Public Scholarship

How do we count and value public scholarship in anthropology? — Do we count and value public scholarship in anthropology? — And, how do we do it at the time of tenure and promotion?

Some departments of anthropology do value and count public scholarship, and have for a long time. Some have built metrics or possibilities into their evaluation systems for considering public scholarship as a part of one’s intellectual work. Others haven’t. Some universities have made strong statements about the value of public scholarship. Indiana University is a one good example; see their Faculty Learning Community’s work on this, including system-wide guidelines on how to count such scholarship. But most universities do not have formal guidelines or even mandates for public scholarship.

Public scholarship is a key part of anthropology. In some ways, it has been part of our practice for a very long time. In other ways, it feels newly important in today’s political climate. Regardless of the genealogies we might chart for the anthropological commitment to having our scholarship be public, it has sometimes been considered something extra to what we do, or something that falls outside what we count as “real” contributions to the field. Given the move of some departments and some universities, as well as some other disciplines to find ways to acknowledge the value of public scholarship, AAA President Alisse Waterston decided it was time for anthropology to act. Continue reading

Kendzior: In Defense of Complaining

This was meant to be a book review. Instead, it’s an essay about the power—and importance—of complaining.[1]

The book under consideration here is Sarah Kendzior’s The View from Flyover Country, which was published in 2015. In case you don’t know, Kendzior is an anthropologist-turned-journalist whose academic work on authoritarianism turned out to be just slightly relevant to the recent turn of events here in the US (and elsewhere).

People ask me all the time what you can do with a degree in anthropology. Now, thanks to Kendzior, I can suggest that students study the intricacies of autocracies and use their analytical skills to warn fellow citizens of the impending erosion of constitutional democracies.[2] Just for starters.

If you follow Kendzior’s work, you know she is willing to speak out. She is not shy. She doesn’t waver. She was willing to talk about issues that many academics—including myself—are hesitant to address. Ever since I first heard of her work, I respected her willingness to take on the kinds of issues that many academics often save for our closed conferences and pay-walled journals (or, perhaps, our Twitter accounts). I’m not sure if she identifies primarily as an anthropologist these days, but in my view she’s one of the few who is doing the kind of “public anthropology” that many of us talk so much about. This is what happens when the analytical perspective of anthropology is unleashed.

The View from Flyover Country is a collection of essays Kendzior wrote for Al Jazeera English between 2012 and 2014. I read most of these essays when they first came out. But readings through them again was a powerful reminder of issues, and voice, that Kendzior brings to the table. The book is arranged in 5 parts: 1) Flyover Country; 2) The Post-Employment Economy; 3) Race and Religion; 4) Higher Ed; and 5) Beyond Flyover Country. There’s also a Coda titled “In Defense of Complaining” that is so poignant to the present moment I’m going to start—and end—there. Continue reading

Rogue: Scholarly Responsibility in the Time of Trump

What if scholars need to go rogue? If anthropologists need to go rogue? In the USA right now, we are not in normal times, but in a new period of attack on academia and science, on facts and funding, on communities with whom anthropologists conduct their research, and on communities to which anthropologists belong. Our scholarly knowledge is increasingly needed in new political ways. But, how do we act effectively and with an awareness of the issues and risks involved?

On Saturday, February 4, 2017, I gave a talk at Duke University as part of their “Precarious Publics” workshop. My invitation was to speak about public anthropology and the current political moment. The initial title of my talk, decided upon after the election but before the inauguration, was “Political Crisis and Scholarly Responsibility, or, Public Anthropology in the Time of Trump.” After the inauguration, things changed, and so did my title. Amidst not only the Muslim ban/immigration ban, but also the attack on climate change science, including the banning of the open, public sharing of scientific knowledge, and in some cases, the erasure of scientific research conducted during the period of the Obama administration, it was no longer sufficient to simply consider “public” anthropology. Instead, along with colleagues in numerous governmental offices and institutions—from the National Park Service to the EPA to NASA to the White House itself—it was time to think of a rogue anthropology. The new title for my talk, delivered on the sixteenth day of the Trump presidency (and posted here on the sixty-first day) was: “If On the Sixteenth Day … : Rogue Anthropology.” Continue reading

Editing Wikipedia > Writing Letters to the New York Times

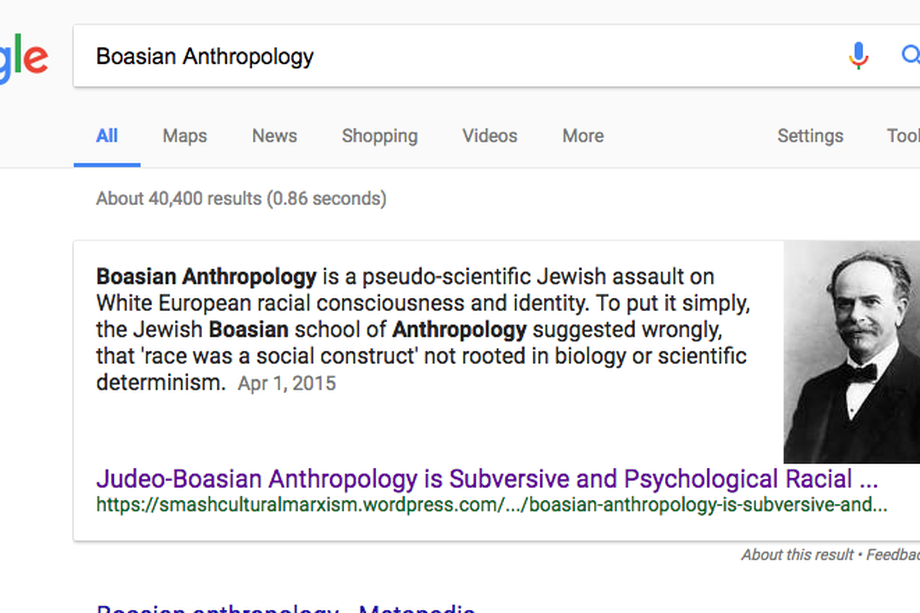

Various bits of social media began vibrating rapidly recently when it was discovered that white supremacists had fooled Google into providing inaccurate information about Boas and cultural relativism. The situation is now apparently resolved, but it isn’t a new problem. Old-timey internet veterans will remember that martinlutherking.org has been run by Stormfront for, like, decades. But this latest kerfuffle should give us the opportunity to think about our priorities as anthropologists writing for the general public today. In a previous post, I argued that there is a difference between the older ‘heroic’ public anthropology and ‘new’, more important public anthropology. Today I want to expand on this point and emphasize that we need shift our conception of public anthropology away from older, moribund genres and to newer, more important, but less familiar ways of reaching the public.

Progressing the Person and Policy

The English word “person” has a long and convoluted history. Though the word itself likely derives from the Latin, persona, referring to the masks worn in theatre, its meaning has evolved over time. One of the biggest conceptual overhauls came in the 4th century AD during a church council that was held to investigate the concept of person as it related to the Trinity. Whereas the Greek fathers defined the Trinity as three hypostases, roughly translated as “substances” or “essences,” the Latin fathers saw them as one hypostasis that could be distinguished by the concept of persona. Because both the Roman Church and the Greek Church viewed each other as orthodox, they brushed off the difference of terms as semantics. Over time, this resulted in a conceptual conflation of the terms, effectively leading to persona encapsulating the notion of both the “role” one plays and one’s “essence” or “character” [1].

Artificially Intelligent, Genuinely a Person

It’s difficult to overstate our society’s fascination with Artificial Intelligence (AI). From the millions of people who tuned in every week for the new HBO show WestWorld to home assistants like Amazon’s Echo and Google Home, Americans fully embrace the notion of “smart machines.” As a peculiar apex of our ability to craft tools, smart machines are revolutionizing our lives at home, at work, and nearly every other facet of society.

We often envision true AI to resemble us – both in body and mind. The Turing Test has evolved in the collective imagination from a machine who can fool you over the phone to one who can fool you in front of your eyes. Indeed, modern conceptions of AI bring to mind Ex Machina’s Ava and WestWorld’s “Hosts,” which are so alike humans in both behavior and looks that they are truly indistinguishable from other humans. However, it seems a bit self-centered to me to assume that a being who equals us in intelligence should also look like us. Though, it is perhaps a fitting assessment for a being who gave itself the biological moniker of “wise man.” At any rate, it’s probably clear to computer scientists and exobiologists alike that “life” doesn’t necessarily need to resemble what we know it as. Likewise, “person” need not represent what we know it as.

Medicine, Technology, and the Ever-Changing Human Person

Though we often take for granted that humans are persons, they are not exempt from questions surrounding personhood. Indeed, what it means to be a person is largely an unsettled argument, even though we often speak of “people” and “persons.” Just as it’s important to ask if other beings might ever be persons, it is also important to ask if humans are ever not persons. In this pursuit, it’s crucial to separate the concept of personhood from notions of respect, love, and importance. That is to say, while a person may necessitate respect, love, and importance, something need not be a person to also demand respect, love, or importance.

When the concept of personhood in humans comes into discussion, it inevitably is punted to the medical community, often in the context of abortion and end of life. When does the heart first beat? When can a fetus feel pain? When does the brain begin/stop producing electrical activity? There is no doubt that advancements in our understanding of human physiology have enlightened discourse on what it means to be both a human and a person. However, the question of personhood is all too often debated solely in light of Western medical contexts. This conflation of physiology and personhood is the same issue that was discussed in my previous post on primate personhood and will be revisited in my next post on artificial intelligence. To escape this quandary we need to consider factors outside of physiology that are important to the concept of personhood, such as the social.

#teachingthedisaster

On Wednesday morning, amid the turbulent mix of feelings that washed across the country and beyond its borders, an anxious existential question took hold of many of us: “what the f***k do we do?” Some seriously considered the need to flee for their lives. Others took to the streets. More than a few folks I know spent the day drunk or in bed. And, by the end of the day, safe spaces for decompression and community care emerged on many college campuses. Part of my own response, one shared by many other faculty, has been: TEACH.

Is This What Democracy Looks Like?

Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Angelique Haugerud.

“America is a shining example of how to hold a free and fair election, right?” asks Bassem Youssef, a comedian and former heart surgeon who is often referred to as “the Egyptian Jon Stewart.” Astute answers to that question about the condition of U.S. democracy often come from foreigners such as satirists, as well as my East African research interlocutors.

Like Jon Stewart and Trevor Noah (The Daily Show), Stephen Colbert (The Colbert Report), and Jon Oliver (Last Week Tonight), Bassem Youssef uses irony and satire to hold a mirror up to society, and to unsettle conventional political and media narratives. State political pressure forced termination of the popular satirical news show Youssef created in Egypt during the Arab Spring. He then moved to the United States, became a fellow at Harvard University’s Institute of Politics in 2015, and in 2016 started a new show in the United States called “Democracy Handbook” on Fusion TV. As foreigners, Youssef, Jon Oliver (British), and Trevor Noah (South African) wittily play off stereotypes of their own home regions as they comment on events in the United States—such as Trevor Noah’s Daily Show segment comparing the 2016 Republican presidential nominee to African dictators.

Can anthropology solve big problems? Imagining Margaret Mead’s response to climate change

Climate change is the nightmare that keeps me up at night. The consensus seems to be that the world will be significantly different within my children’s lifetimes. Many places will be uninhabitable. Many if not most of the world’s great cities, which are built on waterfronts, will be flooded and destroyed by unpredictable weather events and rising oceans. The global refugee crisis will become much, much larger. The food supply will become uncertain. The American landscape and economy will be different in ways I cannot imagine, while India, where I conduct my research, will be a place exponentially more difficult for the millions of people already struggling to get by. There is a degree of uncertainty in these statements, albeit a hopeful uncertainty. Many of the predicted changes are already happening, faster than scientists had thought.

For me, climate change is a crisis so big it is hard to think about at all. Can anthropology help us think through a problem that leaves us feeling overwhelmed? I would argue that yes, anthropological thinking can tackle these thorny problems, and in fact, it’s one of the few approaches that can. The recent AAA Global Climate Change Task Force Report makes this clear, by pointing out anthropology’s unique view on historical and current adaptation. Here, I also want to look back and find some inspiration in the public anthropology of Margaret Mead, who did not hesitate to comment on thorny problems of her day. Continue reading

Would Margaret Mead tweet? On anthropological questions, social media, and the public sphere

Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Rachel C. Fleming

In my first introductory anthropology class of the year, I spoke a bit about the figures I consider “founding” to cultural anthropology, and asked if anyone had heard of them. Franz Boas, I inquired? After a pause, one woman tentatively asked, “Isn’t he the father of anthropology or something?” Yes, ok, close enough. She allowed that she had learned about Boas in another anthropology class. Bronislaw Malinowski? One hand went up in the back. A bearded young man said, “I’ve heard of him, but that’s probably because my girlfriend is an anthropology major.” Yes, that would explain it. And then I asked, Margaret Mead? Silence. I was frankly taken aback. I realize her popular appeal peaked from the 1920s through the 1960s, ancient history to this generation of students. However, she is consistently remembered in our field as possibly the most famous anthropologist to date. She wrote popular columns in national magazines about sexuality, gender, and childhood in the US. Coming of Age in Samoa was a massive bestseller and is still in print. The controversy over her research in Samoa was headline news in anthropology for years. The recent bestselling novel Euphoria fictionalizes her life.

Whatever you may think about Margaret Mead, we cannot dispute that she was a major early figure in what we now call public anthropology. With the efforts of anthropologists such as David Graeber, Barbara King, Tanya Luhrmann, Jonathan Marks, Carole McGranahan, and Paul Stoller, to name just a few, we have a growing voice in the public sphere, spurred along by social media. Yet I cannot help but feel nostalgic for a time when Mead was so well known that she was widely derided in the academy as a “popularizer.” Given the value of anthropological insight for current issues—a point we all strive to make in our classes and elsewhere—I suggest that we could learn from such a popularizer now. In this blog series I will thus reconsider Mead’s work on sexuality, childhood, gender, feminist anthropology, and public change by imagining what she might make of today’s world and the questions and crises we face. Continue reading