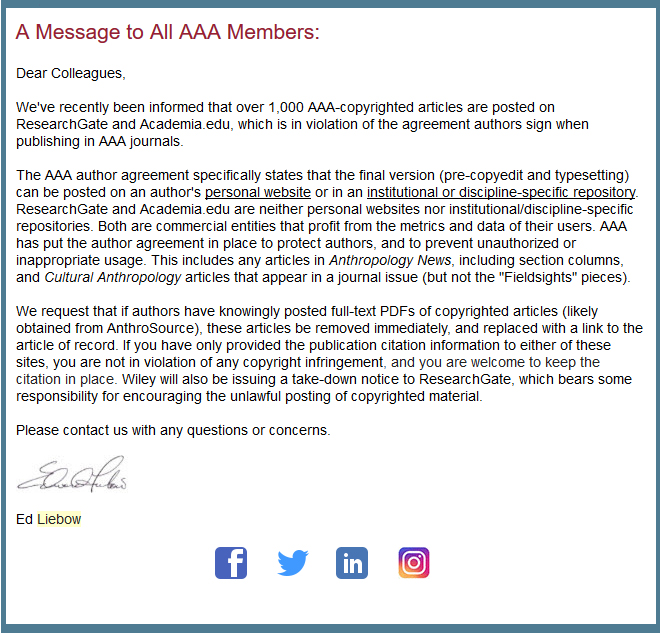

Here we go again. If you’re a member of the American Anthropological Association, you should have received an email this past week (10/17) about avoiding copyright infringement. The message was concise and right to the point: A bunch of members are in violation of their author agreements, and the AAA wants you to take your papers down. Here’s the message in case you missed it:

Basically, the AAA is saying that that more than 1,000 AAA copyrighted articles are in violation of copyright because they have been posted on ResearchGate and Academia.edu. This news is not super shocking, since many of us who publish aren’t particularly informed about the author agreements we sign, let alone how the publishing process works. We just sign those agreements in the rush to publish before we perish…and then sometimes post stuff on commercial sites to make our content “accessible” to the world. Awesome, right? Not so much. This is ultimately to our own detriment.

To quote the Library Loon (as I have before on this site), “The great mass of those who publish in the scholarly literature are pig-ignorant about how scholarly publishing works.” Ouch. But it’s pretty true. How many of you pay close attention to the author agreements you sign? If you did, we might not be having this conversation. Why, you ask? Because you likely signed away your rights, willingly. So when Wiley (or Elsevier, etc) demands that you take your paper down from Academia.edu, they’re just exercising the power you handed to them. As Rex once wrote here on Savage Minds, “if most people realized the way they had signed away their rights to publishers, the open access movement would double or triple in size overnight.”* Continue reading

Back in 1985 Postman wrote a little book called “Amusing Ourselves to Death,” which I happened to use for a class on culture and film I was teaching last year. It turned out to be a prescient book to be reading during the 2016 campaign season (and then some). Postman’s book focuses on the erosion of public discourse in the US, and he faults TV as one of the primary corrosive forces. While there are admittedly some holes in his argument, especially from an anthropological perspective,

Back in 1985 Postman wrote a little book called “Amusing Ourselves to Death,” which I happened to use for a class on culture and film I was teaching last year. It turned out to be a prescient book to be reading during the 2016 campaign season (and then some). Postman’s book focuses on the erosion of public discourse in the US, and he faults TV as one of the primary corrosive forces. While there are admittedly some holes in his argument, especially from an anthropological perspective,