This is my last post as a guest blogger for Savage Minds. I have enjoyed this experience of connecting with so many anthropologists. I want to thank the Savage Minds team for giving me this opportunity to discuss ethnographic writing, and to everyone who offered their thoughts and comments on my posts. Since this is my final contribution, I thought I would end on a personal note and share a short homage to typewriters.

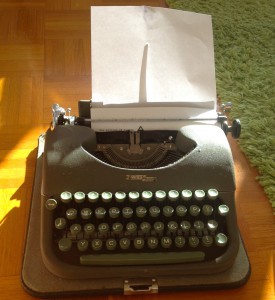

As you may have noticed, many images of old typewriters accompanied my posts on writing this month. These photos are not culled from the Internet, but are pictures of my own growing collection of European manual typewriters, which I now use to write my fieldnotes and my first drafts. I am not a luddite, nor am I paranoid about the NSA reading my fieldnotes. And although I am old enough to have written many early college papers on a typewriter, my trusty Smith Corona was an electric model. I switched to a basic word processor, and eventually to a personal computer as soon as I could afford one. Writing on a manual typewriter is a newly acquired preference.

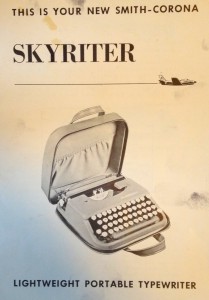

Over twenty years after I retired my electric Smith Corona, my partner surprised me with a vintage Skywriter as a birthday present. The Skywriter hails from the 1950s and was Smith Corona’s attempt at a portable machine that itinerant writers could use on airplanes. Last spring, I began writing research notes, letters, and first drafts of my work on that typewriter, mostly because I loved the clack of the keys, and the fact that email, social media, and the lures of the World Wide Web couldn’t distract me while I worked.