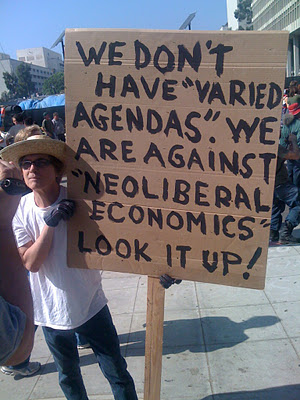

I keep returning to the public sphere as Habermas originally described it as I think about progressive political movements of today: Occupy Wall Street and its global dimensions, Anonymous and its more theatrical and political wing LulzSec, and progressive and independent cable television news network Current. Internet activism, television news punditry, and street-based social movements each work together implicitly or explicitly to constitute a larger public sphere. As scholars we need to resist the temptation of excluding one form of resistance as being inconsequential to social justice or to analysis and instead see all three as working together in a media ecology.

Tag Archives: Visual Anthropology

Anthropologist Bites Dog

I recently had an opportunity to watch José Padilha’s “Secrets of the Tribe” which purports to put “the field of anthropology… under the magnifying glass in [a] fiery investigation of the seminal research on Yanomamö Indians.” This film has been a big success at festivals, screening at Sundance, Hotdocs, etc. and has also been shown on HBO and the BBC, making it one of the most successful recent films about anthropology, yet it seems to have gotten scant attention from anthropologists.

What attention it has gotten has largely been positive, such as this glowing review in CounterPunch, or this blog post by Louis Proyect. A review in VAR was slightly more critical, but not by much. Still, the following comment from Stephen Broomer’s review gets to the heart of the matter:

Padilha’s contribution to this debate is confined within the limits of documentary form. Secrets of the Tribe is a narrative-driven documentary, and as such it privileges dramatic contrast over the reinforcement of facts or proof.

Indeed, I would go much further. The film struck me as little more than tabloid journalism, reveling in salacious scandals, academic cat fights, and conspiracy theories in the name of discussing research ethics and scientific methodology. It reminded me of one of those local news stories where a reporter exclaims how shocked he is to discover that there is prostitution in his city while the camera indulges in digitally blurred closeups of exposed female flesh.

In comparing this film to tabloid journalism I don’t mean to impute Padilha’s motives. Padilha is clearly someone who cares deeply about Brazil’s indigenous population. He also deserves credit for actually interviewing Yanomami for the film. But Padilha is not an anthropologist. As one review put it: “A student of math and physics, Padilha turned to filmmaking after a brief, unsatisfying career in banking.” (He is most famous for “Bus 174” about a hijacked bus in Rio.) For this reason he seems unable to meaningfully engage with contemporary debates about fieldwork practices or the nature of anthropological research.

I don’t really know which bothered me more: the lumping together of pedophilia accusations against Jacques Lizot and Kenneth Good with Patrick Tierney’s accusations against James Neel and Napoleon Chagnon, the fact that the film completely ignored Tim Asch even as it relies extensively on his footage, or the way it presented anthropological epistemology as a simplistic choice between the hard-science of sociobiology on the one hand and mushy-headed cultural relativism on the other.

What really upsets me is that these are serious issues, which warrant serious discussion. By simplifying the scientific debates and lumping them together with pedophilia accusations, the film missed a unique opportunity to make an important contribution to the popular understanding of anthropology. Too bad.

Hipstamatic, Authentic, and (maybe) True

Anthropologists talk a lot about authenticity. I think Edward Bruner put it really well when he said this: “[M]y position is that authenticity is a red herring, to be examined only when tourists, the locals, or the producers themselves use the term” (Culture on Tour, 2005:5). Rather than focus on whether or not something is truly authentic (which can lead to a never-ending debate), Bruner instead argues that it makes more sense to look at how different people think about, debate, and define what they feel is authentic. The focus shifts from a philosophical discussion about truth to an empirical investigation of how different people create and imagine what is and what is not authentic. This, to me, is a really productive methodological tool that anthropology can bring to the table. It’s a good starting point for trying to hash out what “authenticity” is really all about.

So, here’s the question of the day: Can images taken with an iPhone Hipstamatic app really be authentic? Or is this a sign of the end of truth in photography? Continue reading

Eco-Chic Burning Man Hipsters

That curious identity politic that mixes neo-primitive fashion, ecological coolness, spiritual openness, upper middle class ambition, multiculturalism, and conscious consumerism can be coalesced under the moniker eco-chic–an elite contradictory expression of social justice and neoliberalism. It will be explored in the conference Eco–Chic: Connecting Ethical, Sustainable and Elite Consumption, put on by the European Science Foundation in October. The conference organizers see this expressive culture accurately in its rich contradictions. Eco-chic “is both the product of and a move against globalization processes. It is a set of practices, an ideological frame and a marketing strategy.” If you’ve spent anytime in Shoreditch, Haight, Williamsburg, or Silverlake you’ve got some experience with these hip, trendy elites. Ramesh calls them “Burning Man Hipsters.” I’ve been studying new media producers in America and eco-chic describes an important cultural incarnation of these knowledge producer’s value set. As far as anthropology is concerned, meta-categories such as eco-chic, liberalism, or transhumanism that cross cultural boundaries while remaining bound by class, challenge our discipline to revisit totalizing notions such as “culture” and “tribe.”

Eco-chic, like many other socio-cultural manifestations of neoliberalism is rife with contradiction. The fundamental contradiction being that it is a social justice movement within consumer capitalism. The producers of eco-chic goods and experiences are structured by capitalism’s profit motive. Likewise consumers of eco-chic goods and experiences are motivated by ideals that try to transcend or correct the ecological or deleterious human impacts of capitalism. Thus both producer and consumer of eco-chic are caught in a contradiction between their social justice drives and their suspension in the logic of neoliberalism. Eco chic events such as Burning Man and television networks such as Al Gore’s Current TV also express the fundamental contradiction between the social and the entrepreneurial in social entrepreneurialism. How do the contradictions within eco-chic represent themselves in American West Coast’s cultural expressions such as Burning Man and Current TV? Continue reading

I Got Remixed by a Palestinian Hip-Hop Activist

A little over a month ago I uploaded 24 minutes of raw footage of the Palestine/Israel Wall I shot in 2009. This is footage for a documentary I am making about divided cities. I’ve finished the sections on Nicosia, Cyprus and Belfast, North Ireland and I’ve finished shooting but not editing this story on East Jerusalem. Unedited and with its natural sounds I thought it was gritty and evocative enough to stand alone on YouTube. I uploaded it and titled it “Palestine Apartheid Wall Raw Footage.” Last week I got a YouTube message from user WHW680 who kindly informed me that he remixed my footage into the French pro-independent Palestine hip-hop video “the Wall of Zionist Racist Freedom for Palestine.” Shocked and honored I watched the video.

Artistically, WHW680 doesn’t use the shots I would; he doesn’t get the projection ratios right; I wouldn’t quite be so intense with the title; and he cuts the edits too early or too late, making the viewing experience choppy. I am being intentionally superficial here for a reason, as I am trying to express the first round of mental dissonance experienced when remixed. As a cinematographer it is an enlightening if challenging ordeal. It gets deeper, too, when your work is not only remixed in a way that challenges your technical and artistic vision but is used politically in surprising ways.

The footage was used to make a music video for the track “Palestine” by Le Ministère des Affaires Populaires, a popular Arab-French hip-hip group in Paris, off of “Les Bronzés Font du Ch’ti” described as “an album that sounds like a call to rebellion, insurrection and disobedience but also solidarity.” They tour Palestine, including Gaza. The music is fantastic, mixing breaks, good flows, meaningful lyrics, and longing violins. Obviously I can get behind the activism of a liberated Palestine but becoming a tool for propaganda, despite my agreement with it, without my vocal consent, is a creatively dissonant experience.

Political semiotic engineering for the right causes I can dig, but agency denying actions are experienced as a type of cognitive violation nonetheless. The quintessential sign of this is the final few second of the video. After the footage ends and while the music still lingers, the words “Freedom, Return, and Equality,” and “Free Palestine-Boycott Israel,” and www.bdsmovement.net circle a Palestinian flag. This final frame essentially brands this video for the BDS Movement, a civil rights organization focused on “boycotts, divestment and sanctions (BDS) against Israel until it complies with international law and Palestinian rights.”

This isn’t “my” footage anymore, WHW680 generously cites me in the description, but the semiotic potential of the footage previously shot by me is mobilized for the BDS Movement. The aesthetic and the political fold into each other in remix activities in which preceding agencies, my own as cameraman, is incorporated or replaced by the technical agencies of the French remixer, WHW680, and reformulated into the political vision of the pro-Palestinian BDS Movement. Which is all good, but it gives me a new look at remix culture.

This experience has forced me to eat some of my words. Remix culture isn’t a myth. I agree with my earlier detractors who stated that it isn’t about the volume of the activity nor the impact of this remixed song or that music video. I would add something more. Being remixed is personally transformative for those being reformatted by values and practices beyond their control. Not only does remix challenge jurisprudence and liberalism, and present new modes of knowledge production, it also modifies the subjective constitution of agency in artistic and political social sphere.

What Tim Hetherington Offered to Anthropology

On March 15th, I moderated a panel at RISD called Picturing Soldiers: The Aesthetics and Ethics of Contemporary Soldier Photographs featuring photographers Lori Grinker, Jennifer Karady, Suzanne Opton, and Tim Hetherington, who as killed today in Libya.

On March 15th, I moderated a panel at RISD called Picturing Soldiers: The Aesthetics and Ethics of Contemporary Soldier Photographs featuring photographers Lori Grinker, Jennifer Karady, Suzanne Opton, and Tim Hetherington, who as killed today in Libya.

One of the amazing things about the work of each of these artists is how resonant it is with what we do as anthropologists. Like ethnography, their images are not simply about ‘documentation.’ They are about conveying something of lived experience that allows us, provokes us, to ask questions about how some particular lives come to look they way they do. They invite us to linger on the lives of soldiers long enough to think about how they are, and also are not, like others.

It strikes me that in our disciplinary conversations about what various modes of anthropological engagement might look like, we often fail to recognize the possibilities of such resonances. These possibilities are especially promising when the lives we explore are characterized, in one way or another, by war. Here, issues of politics and ethics lie both close to the surface and close to the bone. Tim Hetherington’s work was powerful proof of these possibilities.

For example, he said many times that he hoped Restrepo, his thoroughly ethnographic Afghanistan war documentary, co-directed with Sebastian Junger, would offer a new and more productive starting place for thinking about the war and US military intervention.

As Tim put it in an excellent interview at Guernica where he responds to Leftist criticism of the film:

While moral outrage may motivate me, I think demanding moral outrage is actually counter-productive because people tend to switch off. […] Sure, the face of the U.S. soldier is the “easiest entrée into the Afghan war zone” but it has allowed me to touch many people at home with rare close-up footage of injured and dead Afghan civilians (as well as a young U.S. soldier having a breakdown following the death of his best friend). Perhaps these moments represent the true face of war rather than the facts and figures of political analyses or the black and white newsprint of leaked documents.

In a more personal mode, Tim offered the experimental film Diary, which reflects something of the compulsions, rhythms, and senses of his movement into and out of ‘zones of killing’, as he suggested we might think of such spaces. Here too, we can find resonances with anthropological explorations of the particular vertiginous experiences of being in and out and in such spaces of violence, and of the uneven geographies of deadly violence.

News continues to unfold about the incident in Libya that may have also killed photographer Chris Hondros, and that seriously injured photographers Guy Martin, Michael Christopher, among others. And as we continue to hear more of Tim Hetherington’s death, and more remembrances of his life and work, I’ll also be thinking about what his work, and the work of other artists and journalists, has to offer us anthropologists; the places where our various projects meet, and the possibilities for thinking and acting that might begin from there.

Critical Pessimism & Media Reform Movements

The American satellite television network Free Speech TV asked me to write up a blurb for their monthly newsletter about my participatory/observatory trip with them to the National Conference on Media Reform in Boston. This is my attempt at what Henry Jenkins calls “critical pessimism”–an “exaggeration” that “frighten readers into taking action” to stop media consolidation, exclusion, and the absence of televisual diversity.

Free Speech TV at the National Conference on Media Reform

From its inception in 1995, Free Speech TV’s goal has been to infiltrate and subvert the vapid, shrill and corporately controlled American television newscape with challenging and unheard voices. Fast forward to 2011, and in the age of viral videos, social media and ubiquitous computing, the same issues persist.

An excellent young pro-freedom-of-speech organization, Free Press, called all media activists to Boston for the National Conference on Media Reform (NCMR), April 8-10, to celebrate independent media and incubate strategies to fight the tide of corporate personhood, monopolization in communication industries, and the denial of access to the public airwaves.

These are issues FSTV has long fought, first with VHS tapes of radical documentaries shipped to community access stations throughout the nation, then through satellite carriage in 30 million homes, and now via live internet video and direct dialogues with the audience through social media.

FSTV was at NCMR in full force, covering live panels on everything from the role of social media in North African revolutions to media’s sexualization of women; developing strategic relationships with print, radio, internet and television collaborators; interviewing luminaries like FCC Commissioner Copps; and inspiring the delegates by opening up the otherwise closed and corporatized satellite television world to the voices of media activists fighting for access and diversity during a frankly terrifying period in American media freedom.

One question haunted the many stages, daises and dialogues at the NCMR: Is the open, decentralized, accessible and diverse internet – by which media production, citizen journalism and community collaboration have been recently democratized – becoming closed, centralized and homogenous as it begins to look and feel more like the elite-controlled cable television system?

For example, while we were in the conference, the House voted to block the FCC from protecting our right to access an open Internet. The mergers of Comcast and NBC-Universal and AT&T/T-Mobile loomed behind every passionate oration. And yet FSTV was there to document when FCC Commissioner Copps took the stage stating he would resist the denial of network neutrality and such monopolizing mergers.

Internationally, examples of the power and problems of the internet exist. The Egypt-based Facebook group “We are all Khaled Said” had 80,000 members, many who amassed at Tahrir Square on January 26, instigating a wave of democratization that began in Tunisia – also fueled by social media – and hopefully continuing to Libya. Two days later, however, the Mubarak regime was able effectively to hit a “kill switch” on the internet and target activists using Facebook for arrest, an activity that worked against the desires of the repressive regime. At the NCMR, Democracy Now! reporter Sharif Abdel Kouddous said, “Facebook was down … so they hit the streets. It had the reverse desire and effect that the government wanted to happen.”

In 2010, Reporters Without Borders compiled a list of 13 internet enemies – countries that suppress free speech online. The U.S. wasn’t on the list, but U.S. companies Amazon, Paypal, Mastercard, Visa and Apple were pressured to cut digital and financial support for whistleblowing WikiLeaks. The point is obvious: A vigilant press aided by an open, uncensored and unprivatized internet are necessary yet threatened and are the focus of FSTV’s coverage at NCMR.

FSTV embodies that ancient movement of ordinary people taking back power from entrenched elites. Today, every issue, from class inequality to ecological justice – is a media issue. However, our media sources, from journalists to internet and television delivery systems, are being co-opted by monopolizing corporations and lobbyists. As an independent, open and interactive television network, FSTV is an antidote to the problems facing free speech and democracy as more media power is centralized in fewer hands. Thankfully, as we found out in Boston, FSTV is not alone in this dangerous and difficult operation of media liberation.

Jenkins hyperbolically describes “critical pessimists” as people who “opt out of media altogether and live in the woods, eating acorns and lizards and reading only books published on recycled paper by small alternative presses”. This is a false exaggeration of a movement that is providing a necessary check on corporate power and mindfully working for greater civic, community, and citizen involvement in media production.

Participation, Collaboration, and Mergers

I work at UCLA’s Part.Public.Part.Lab where we investigate new modes of co-production and participation facilitated by networked technologies. Internet-enabled citizen journalism such as Current TV, public science like PatientsLikeMe, and free and open software development like Wikipedia are key foci. In the lab I investigate the vitality or closure of a moment of freedom and openness within cable television, news production, and internet video when the amateur and the alternative disrupted the professional and the mainstream. What are the promises and perils of social justice video in the age of internet/television convergence? Will internet video become as inaccessible, vapid, and homogenous as cable television? In our recent paper, Birds of the Internet: Towards a field guide to the organization and governance of participation, we draft a guide to identify two species flourishing in the internet ecology: what we call “formal social enterprises,” which include firms and non-profits, as well as the “organized publics” the enterprises foster or from which they emerge. These two types share a vertical or inverted relationship, power comes down from visionary CEOs and charismatic NGO directors to provoke rabid social media production, or a viable movement foments amongst grassroots makers that percolates upwards towards the formation of semi-elitist institutions. In light of this research and with a discreet fieldwork experience to think through I would like to clarify and address three types of social interaction: participation, collaboration, and mergers. Continue reading

Learning About Consent

The Spring semester starts today here in Taiwan, and this semester I will once again be teaching a course on production methods in visual ethnography. One of my requirements each semester, the one which most bothers my students, is that their final work be posted to the internet. This is a problem for them because it is much harder to get consent from your subjects for a student project used for class than it is for a project which will be posted to the internet for anyone to see. But for me, that is the first, and perhaps most important lesson my students will learn from the class.

We spend a lot of time talking about ethnography as a product, and even about the ethical issues involved in “shared anthropology,” but it is almost impossible to teach someone how to gain the trust of their research subjects. There is no one-size-fits-all approach because the obstacles to gaining such consent will vary from project to project. While I can’t offer pre-packaged solutions, I can advise students how to handle such obstacles without giving up. Patience and persistence are skills which many students have yet to learn. There are also techniques they can use in the filmmaking process to work around limitations placed on them by their subjects. There is a tremendous wealth of ethnographic knowledge to be gained from working through these obstacles.

One of my students this semester wants to work with a local hearing impaired community. We were both surprised to learn that the members of this community lack the necessary Chinese literacy to be able to read and understand a consent form. Continue reading

Swarm

A highlight of the recent AAA conference in New Orleans was a visit to one of the three art galleries participating in Swarm: Multispecies Salon 3, one of the new “inno-vent” functions spun off from the usual conference proceedings. There was a “Multispecies Anthropology” panel at the conference itself, but sadly it was timed to overlap with the very panel I was participating in. As a multimedia art installation Swarm was highly stimulating and a lot of fun too, I would have loved to see it tied more directly to contemporary cultural anthropology and theory. Fortunately I can turn to the journal Cultural Anthropology Vol. 25, Issue 4 (2010), a special theme issue edited by some of the co-curators of Swarm that explores the intersections of bioart and anthropology, humans and non-human species, science and nature.

Saturday evening, after the SANA business meeting and a catfish po-boy, I slinked back to my cheap hotel for a change of clothes and to get the address of The Ironworks studio on Piety Street. It turns out hailing a cab in New Orleans on a Saturday night can take awhile, especially when you’re in the CBD. And when I did get a cabbie, he confessed to not knowing where Piety Street was and his sole map seemed to be a tourist brochure which only listed major intersections. (“Here put these on,” and he gave me his reading glasses as if this would help.) I bargained that waiting to catch another cab would take longer than navigating with a lost cabbie and so we set sail on the streets of New Orleans.

After the confusion, a train, and about six blocks of streets without names we arrived. The Ironworks was an ideal setting for this experiment in art and anthropology. At the end of a city neighborhood, under the comforting glow of the street lamps, the building suggested a past life as a warehouse or place of light industry. Inside a high fence folks gathered around a keg of beer or perched on picnic tables on the edge of a interior yard whose distance brought darkness and a sense of privacy. This is where the robots roamed, clacking and blinking.

Inside I soon found my friends, alums from my alma mater New College – many of us became professional anthropologists – had agreed to swarm the Swarm. Much to my surprise there were even some undergrads who spotted me right away by my tattoo of the school logo and a fellow from my class who became a criminal lawyer and now lived right down the street. Also there were tamales. And a band of noise musicians. It was good crowd to be in, a mix of ages, anthropologists and artists.

Digital Labor

My colleague Ramesh Srinivasan and I just submitted an article to a journal in which we analyze social entrepreneurs’ digital labor practices. The argument we are making is that one needs to focus on (1) organizational missions, cultures and histories, (2) the nature of the labor (its level of creativity or its invocation of routinized, uncreative time-motion studies!) and the level of agency for workers to choose this labor versus various alternatives, and (3) the level of capitalization of the labor, notably who profits and to what extent from the contributed work. Our case studies, Samasource, a digital labor firm that brings digital work to developing world populations, including refugees and women, and Current TV, a cable network that self describes as “democratizing” documentary production, maintain an interplay between for/non-profit and social empowerment/exploitation. Instead of waiting the 4 months for reviews, or 8 months for publication we’d love some real time feedback on some of the more illustrative examples and concerns that drive this research. (I’ll be presenting this analysis at the American Anthropological Association meeting on Friday at 5 if you prefer embodied engagement).

The Pioneer Age of Internet Video (2005-2009)

There is a touch-screen internet networked television mounted on a wall in a middle class living room. You turn it on with a touch and rows of applications organized as colorful little boxes are revealed. You are familiar with the choices because they are the same as what is displayed on your mobile phone. In this apparent cornucopia of choices are hundreds of apps to click to watch CBS dramas, New York Times video segments, CNET interview programs, Mashable tweetfeeds, and CNN live broadcasts. Or you can rent a movie from Apple’s iTV, Google TV, Amazon, or YouTube Rentals suggested to you based on your shopping preferences as gathered from your GPS ambulations. You want to show your friend a funny video that was recommended to you earlier in the day so you click on the YouTube Partners app and it appears on the screen.

You crave a different meme, something old school, circa around 2009. You could go to the YouTube Classics app, but strangely your favorite video never made it to 100 million views and so wasn’t promoted to YouTube Classics. Your television system is connected to the internet but the public internet browser app is buried in the systems folder on your networked TV. Besides, if you could find the browser app you can’t find a keyboard to type out search terms. You drop the idea of following a personal impulse and go with what you can see through the window of the professionally curated suite of applications.

This description of a limited and safe television viewing experience of the future is meant to evoke a feeling that the limitless content and freedom that we associate with internet video is quickly being truncated by the hardware and software engineers in cahoots with the content app designers to make a much more safe, convenient, and professional internet. This is quite easy to see in the world of internet video—once the land of the most subversive, graphic, and comic content possible—is now being overhauled by professionals producing, curating, optimizing, and streaming ‘quality’ videos to homes on proprietary hardware. Many of us interested in the democratization of media, the absence of conglomerate consolidation, the presence of “generative” digital tools, video activism, and indigenous media should be concerned by these trends. This era will be seen as the historical pioneering era of internet video idealism (2005-2009).

Earlier this month, in re-introducing Apple’s internet connected TV set top box, the iTV, Steve Jobs claimed that people want “Hollywood movies and TV shows…they don’t want amateur hour.” What Jobs is saying is that we are entering a new era of professionalism—gone is the wild Darwinian kingdom of video memes, the meritocracy of the rabble rousers, the open platforms equally prioritizing the talented poor as well as the rich. Jobs has never been one to parrot the ‘democratization of media’ ideal. Never one championing collective design or the wisdom of the crowd (if only to fanatically buy his hardware), Jobs firmly believes in the auteur, the singular virtuosity of the genius designer, engineer, and director to make a professionally superior object of art and function. The upcoming golden age of ‘quality’ professional content will be ruled by Jobs and his ilk at HBO, Pixar, Hulu, LG, and Vizio.

Jobs’ vision is but one example showing that the pioneer age of the free and open culture of internet video is ending. Current TV, from 2005-2008, aired 30% user-generated documentaries and produced a cable television network that modeled democracy. Today they are taking pitches only from top Hollywood TV producers. The YouTube Partner’s program, like the very talented Next New Networks—the talent agents for Obama Girl and Auto-Tune the News—culls the ripest and most viral video producers from YouTube and optimizes them for the attachment of profitable commercials. Once pruned and preened, these YouTube cybercelebrities are promoted on the hottest real estate on the internet, YouTube’s frontpage, making 6-figures for themselves while finally making YouTube profitable.

Subcultural activities going mainstream is nothing new, the radical 60s cable guerilla television crew, TVTV, went from making ironic investigations into the 1972 Republican and Democratic conventions to making regular puff pieces for broadcast. World of Wonder, the queerest television company in Hollywood, has been bringing the sexual and gender underground to mainstream cable television for decades. For examples, see my documentary on World of Wonder.

But it is the first example regarding IPTV—internet-based direct to consumer ‘television’ such as Apple’s iTV—that will bring only the best of internet video to the home that most concerns me. The professional domestication of internet video in the home, I fear, will forever wipe out the memory of the wicked and subversive video memes of the YouTube past. With it will go the very ethos of participatory video culture. My colleagues in the Open Video movement can collectively design the hell out of open video apps, editing systems, protocols, and videos standards but no one using these free and open source video systems will be seen if proprietary IPTV covers both software and hardware, internet and television, in both the home and the office.

The process I am describing can best be articulated as a historical process of professionalization. The wild world of amateur video—its production, promotion, and distribution procedures—is moving from the realm of prototyping, beta-testing, and experimentation to expert production, algorithmic optimization, and alpha release five years after its debut on YouTube and Current TV. This professionalization is a historical result of 5 years of industrial development, individual trial and error, and profit-focused talent agencies and creative thinktanks. It is also a product of the historical convergence of the internet and television hardware, as well as the corporate consolidation of content and software around the idea of the app—a professionally designed hardware/software/content peephole into a small fraction of the internet. More anthropological however is the historical transformation of the subculture into the culture. This has been happening forever and is the engine of popular culture and we shouldn’t be so hip and retro as to bemoan it. But we should be concerned with the loss of that realm of artistic and political potential encoded in the free and open internet. The “golden age” to follow this pioneering phase will be as innovative as the golden age of television as we welcome the equivalent of I Love Lucy, Friends, and Lost and along with it the return to spectatorism, canned laughter, and the proliferation of middle class values.

TV Free Burning Man

Next week as many as 50,000 people will inhabit Black Rock City, a temporary metropole constructed by volunteers for a week of personal expression and community celebration on the barren alkaline plains of a Nevada desert a half-days drive from Silicon Valley. This is Burning Man, a radically participatory event where a lot of people who labor in the digital creative industries work out collaborative utopias that make their way–the theory goes–into the social networking software and platforms they make and ask us to populate with our creative surplus, communal energy, and visually expressive humanity. The techno-culture historian Fred Turner states that Burning Man is a ‘sociotechnical commons’—the cultural infrastructure for the digital media industries of California. This is an attempt to document how and why Burning Man is a “proof of concept,” “beta test,” and practical experiment for the engineering of networked publics.

Current’s first idea about content producers was not to crowdsource content through the VC2 program. They didn’t intend to mine the producing audience for TV-caliber video submissions. Current originally planned to hire 20-30 digital correspondents to travel the world making content. A Current employee related to me how the programming executives, fresh from recent excursions to Burning Man in the early 2000s, used the open participatory model of Burning Man to argue against the exclusivity of the digital correspondent model by asking, “like Burning Man, why wouldn’t we let everybody in who wants to participate?” That spirit carried into the creation the VC2, a project to empower any amateur documentary producer to make content for television. This was the impetus behind the first user-generated television network.

From 2005-2008 Current’s website was www.current.tv. It was a space dedicated to VC2 producers to upload and critique short documentaries. In 2008, upper management decided that this was too elitist and they wanted more traffic so they put together a group of marketers, engineers, and creative executives to envision the new website, current.com. One of those creative executives, Justin Gunn, went into the first meeting to brainstorm current.com and

…hung up a map of Burning Man and I took an astronomy magazine and cut out pictures of stars and star clusters, and galaxies and galaxy clusters, and superclusters really beautiful Hubble imagery and positioned it around the Burning Man map and I looked at [my colleagues] and said, ‘that is what we are going to make.’ And they said,’ what is that?’ And I said, ‘OK, work with me here. We are going to start with the organizational principle of Burning Man, it is a very light, lean organization. I could be wrong here but there is something like 12 full-time employees around the year everything else is all volunteer labor. But they build the structure, they set the rules, they define the parameters and then they invite anyone, anyone to come and do whatever they want as long as they stay within the confines, abide by the rules, and follow the predetermined parameters—they can do whatever they want.’…You start with an organization principle, a framework, here is how this thing works, here is the lattice, but it is empty, we will do a few key things, and we will invite anybody in as long as they abide by the rules and play within the framework, they can build whatever they want. So the constellations and star clusters were meant to represent constellations of information.

Using celestially graphic metaphors for the digitally engaged public they hoped to network together Gunn sought to inspire his co-workers to make a system as open and empty–and as charged with possibility–as the desert of Black Rock before the gates of Burning Man swing wide.

Using their shared interests in participatory community, self expression, and technology as a platform for dialogue–as well as their proximal offices mere blocks from each other in the Silicon Valley outpost of SoMa in San Francisco– producers at Current and organizers of Burning Man began to scheme about a more dynamic relationship. TV Free Burning Man was a result. Combining professional and amateur field production with a televisual aesthetic of first person documentaries and tone poems, the for profit mass media television firm Current produced content live from the playa for four years, 2005-2008. Considering Burning Man’s imperative to avoid all forms of commercialization and the strict media permitting process to even use a still camera at Burning Man, TV Free Burning Man is a testament to the shared ideals and aesthetics of Current and Burning Man.

——————————–

I’ve attempted to link an outrageous event to important technological and economic digital systems used by billions of humans. The goal is to see how internet practices in virtual spaces are coconstituted by actual world practices in material spaces. Savage Mind writer Rex coolly said CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s goal with Facebook is to “scaffold” sociality–strap supportive beams to the human-to-human communication network that presently exists or might not exist without the structured arena. Rex has it right. Social media and social events, like the virtual and the actual, are coconstructed. And yet, something still trumps this transcendence of body-mind duality.

The commercial imperative looms over the users of corporately-made social media just as the end of the week at Black Rock City haunts the freedom-accustomed Burner. In a series of moves, Current has increasingly pulled back from their mission to democratize media production. In a tense economy and with venture capitalist money running thin, Current has moved to capitalize on its major asset, its cable license, through abandoning the VC2 program and relying on traditional professional programming.

Burning Man, on the other hand, remains a valiant, excessive, and privileged materialization of the ideal sociality coded into and by internet culture. Last year around this time I wrote about the emerging tourism industry in Black Rock City, But for now, the Black Rock Foundation does a tremendous job with a skeleton staff, grants art funds to hundreds of artists, and facilitates a relatively commercial free environment. As a non-profit with a seasonal ecstatic event, Burning Man has an easier job than Current of retaining its mission, a for-profit firm in a fiercely competitive TV market responsible for 24 hours of programming 365 days a year.

Openness, liberation, transparency, relativity, democracy, trust, non-privacy, and collaboration are the shared origin myths of the activists and planners of the internet and Burning Man. These ideals are coded into digital architecture in Silicon Valley and other areas around the Black Rock Desert and distributed for free use throughout the world. These digital social systems and event organizations are molded by their missions and driven by the necessity to optimize the growth of their organizations. Every ideal has a shelf life cut short usually by the profit necessity. The compromises to the mission that commercialization requires are the instances to monitor when adjudicating the sustainability of the social entrepreneurship model.

Facebook as a Potlatch

Are you familiar with the concept of a gift economy? It’s an interesting alternative to the market economy in a lot of less developed cultures. I’ll contribute something and give it to someone, and then out of obligation or generosity that person will give something back to me. The whole culture works on this framework of mutual giving. The thing that binds those communities together and makes the potlatch work is the fact that the community is small enough that people can see each other’s contributions. But once one of these societies gets past a certain point in size the system breaks down. People can no longer see everything that’s going on, and you get freeloaders. When there’s more openness, with everyone being able to express their opinion very quickly, more of the economy starts to operate like a gift economy. It puts the onus on companies and organizations to be more good, more trustworthy. It’s changing the ways that governments work. A more transparent world creates a better-governed world and a fairer world.

Kapah (Young Men): Alternative Cultural Activism in Taiwan

This post is an occasional contribution by Futuru C.L. Tsai. Futuru recently got his Ph.D. in July 2010 from the Institute of Anthropology at National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan. His dissertation is entitled Playing Modernity: Play as a Path Shuttling across Space and Time of A’tolan Amis in Taiwan. He was a training manager in a semiconductor corporation originally but quit to pursue a Ph.D. in anthropology. Futuru is also an ethnographic filmmaker and writer, who has produced three ethnographic films including Amis Hip Hop (45 min, 2005), From New Guinea to Taipei (83 min, 2009), and The New Flood (51 min, 2010), and a book: The Anthropologist Germinating from the Rock Piles (Shiduei zhong faya de renleixuei jia) (Taipei: Yushanshe, 2009).

Kapah (Young Men) /Lyrics & Music: Suming

Are there any young men who can sing out there? Are there any men who can dance? Are there any men who are good in school? Are there any men who are good at making money? Are there any men who are good at planting crops? Are there any men who are good at gathering? Are there any men who are good at spearing fish? Are there any men who are good at cooking? Are there any fun men out there? Are there any strong men? Are there any hard workers? Are there any men that work together? Yes, there are the young men from A’tolan!

A brand new music album with complete Amis lyrics by the Amis artist, Suming, was released in May 2010. It is not the first Amis music album but is the first one attempting to crossover into popular music market in Taiwan, combining indigenous melodies such as Amis polyphony and flutes together with techno-trance, hip-hop, and Taiwanese folk music. Among these songs, “Kapah,” which means “young men” in the Amis language, is the theme song. Lungnan Isak Fangas, a documentary filmmaker, who is also an Amis, made two music videos for this album, one of them is Kapah. Both the song and the music video not only represent aspects of local A’tolan Amis culture but also attempt to make this culture appealing to Taiwanese society at large.

There are currently 14 indigenous ethnic groups (referred to as “Aborigines”) officially recognized by the Taiwan government. The Amis is the largest of these austronesian speaking ethnic groups in Taiwan. There are two conspicuous characters of Amis society and culture relevant to understanding this video: One is that it is widely considered a matriarchal society, although its status as such is still under debate. Nonetheless, the image of the mother holds a central place in Amis society. The other one is the age-grade system with its rigid regulations. Age sets are organized around males who have passed the coming of age rites in the village within a given time period. Each age set (kapot) will include men born within a few years of each other. It is the main political unit, handling the affairs of both outsiders and insiders.

The song Kapah differs from earlier indigenous music in its depiction of indigenous modernity. Continue reading