Foucault asks “Can the market really have the power of formalization for both the state and society?” (Foucault 2008: 117, originally 1978-79). House Budget Chairman Rep. Paul Ryan is convinced it can. He outlines it happening in the 2012 and 2013 fiscal year budgets. The impact of this neoliberal fantasy on democracy is stated by Couldry: “‘Democracy’ operated on neoliberal principles is not democracy. For it has abandoned, as unnecessary, a vision of democracy as a form of social organization in which government’s legitimacy is measured by the degree to which it takes account of its citizens’ voices” (Couldry 2010: 64). What is the impact of the dearth of diverse progressive voices on public and private media within the hegemonic public sphere?

The Nation states that the GOP’s 2013 budget or the “Ryan Plan” helps the very wealthy, corporations, Pentagon, and health insurance companies while forcing the poor, elderly, disabled, and middle class to sacrifice (Zornick 2012). President Obama called the budget “social Darwinism.” A great term, curiously investigated by the Washington Post. Back in February, 2011, during the last federal budget battle, the New York Times claimed that the GOP targeted to slash funding for job training, environmental protection, disease control, crime protection, science, technology, education, and public media (Editorial 2011). It is a theory of classical liberalism that as these issues of national importance are proposed and debated it is fundamental to the workings of democracy that citizens have diverse information options. This is the job of journalists, newspapers, television news — “the media” — whose investigate capacities have been gutted by parent companies’ market fundamentalism and whose federal funding, when it barely existed, is under attack. Six bills were proposed in 2011 to eliminate federally funding PBS (Tomasic 2011). In this neoliberal media logic, if it fails the single criteria of increasing capital, it misses the cut.

The same week the draconian 2013 Ryan Plan was revealed saw the elimination of two paternalistic guardians of the “American public sphere” –the Media Access Project (MAP), a public interest law firm and 40-year veteran resisting the deregulation and privatization of public media resources. And, most dramatically, Keith Olbermann was fired from Current, a cable television news network. Like him or hate him, he is one of the few television newscasters willing to bluntly critique such instances of neoliberal governmentality on that most hegemonic if media systems: television. As both private public interest and not-for-profit public interest media institutions falter, and federally funded public media systems are assaulted, how will diversity in the American public sphere survive?

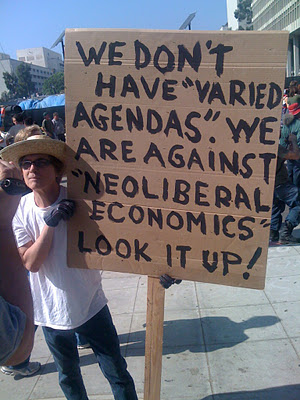

I need to briefly address the following normative notions: neoliberal governmentality and the hegemonic or American public sphere.

MAP and Olbermann focused on diversifying the programming within the hegemonic public sphere. They see themselves, their work, and their information as central to dominant national issues within a single American public sphere. They are not interested in producing the conditions for a subaltern counterpublic as Nancy Fraser (1992) describes. Their interest is in competing on a national-level with the likes of Fox News, MSNBC, and other media giants. MAP and Olbermann sought to contribute diverse voices into a single, national, or American public sphere. Does it exist? No. Fraser is right. There are overlapping fields of public spheres. But the hegemonic public sphere is a type of emic model or frame, non-existent on the level of day-to-day discourse, that these media reform broadcasters draw from. More abstract and less polemical, yet comparable with the concept of the “mainstream media,” the hegemonic public sphere is a goal or target for the progressive cultural interventions of these media reform broadcasters.

Foucault provides a cogent definition of neoliberal governmentality in his exquisitely readable lectures at the College de France in 1978-1979. “What is at issue” said Foucault, “is whether a market economy can in fact serve as the principle, form, and model for a state” (Foucault 2008: 117). The result is market statism, or corporatism, which, in an extreme version, is fascism. This is diametrically opposed to the social liberalism advocated by Olbermann and MAP in which the state is focused on non-market social projects. It isn’t corporate liberalism either where the government in public discourse supports social liberalism but that practice is performed by subsidized corporations (Streeter 1996). An example of corporate liberalism comes from the presumed GOP candidate for the 2012 presidential election. Governor Mitt Romney addressed a crowd at a primary campaign stop in Iowa in November. At this event Romney says he won’t gut the Corporation for Public Broadcasting but he will require it to “have advertisments.” Romney doesn’t want to “Kill Big Bird” he just wants it to be on life-support from American corporations. Rather, the Ryan Plan is neoliberal governmentality where social liberal projects are negated and replaced by market fundamentalism. It is this reduction of government functions to market logic that Olbermann and MAP once raged against.

So with the departure of Olbermann and MAP the monolithic American public sphere is less diverse and less capable of engineering the conditions for access for diverse voices. Nick Couldry’s Why Voice Matters: Culture and Politics after Neoliberalism (2010) directly addresses how neoliberal governmentality dampens voice through looking at US and UK television. He defines voice as referring to the process of individuals or communities using media to build reflexive and historical stories. Voice, for Couldry, is socially grounded, provides for reflexive agency and is an embodied force. Voice can be injured or denied by rationalities that perceive voice as an externality of market logic. Thus “valuing voice means valuing something that neoliberal rationality fails to count; it can therefore contribute to a counter-rationality against neoliberalism” (Couldry 2010: 12-13). Without Olbermann’s voice and MAP protecting the legal and political conditions for voicing, how will the American public sphere survive this assault by the flexible tactics of neoliberal governmentality?

@@@

Now, dear Reader, to reward you making it this far here are some hilarious videos that illustrate my points from the comic geniuses of Mitt Romney, President Obama, Cenk Uygur! Cue the laugh track after each video. Continue reading →