Decolonizing Anthropology is a new series on Savage Minds edited by Carole McGranahan and Uzma Z. Rizvi. Welcome.

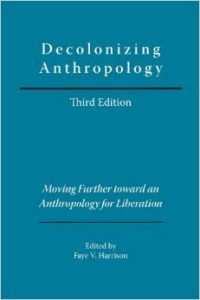

Just about 25 years ago Faye Harrison poignantly asked if “an authentic anthropology can emerge from the critical intellectual traditions and counter-hegemonic struggles of Third World peoples? Can a genuine study of humankind arise from dialogues, debates, and reconciliation amongst various non-Western and Western intellectuals — both those with formal credentials and those with other socially meaningful and appreciated qualifications?” (1991:1). In launching this series, we acknowledge the key role that Black anthropologists have played in thinking through how and why to decolonize anthropology, from the 1987 Association of Black Anthropologists’ roundtable at the AAAs that preceded the 1991 volume on Decolonizing Anthropology edited by Faye Harrison, to the World Anthropologies Network, to Jafari Sinclaire Allen and Ryan Cecil Jobson’s essay out this very month in Current Anthropology on “The Decolonizing Generation: (Race and) Theory in Anthropology since the Eighties.”

These questions continue to haunt anthropology and all those striving to bring some resolution to these issues. It has become increasingly important to also recognize the ways in which those questions have changed, and how the separation between Western and NonWestern is less about locality and geography, but rather an epistemic question related to the colonial histories of anthropology. Decolonization then has multiple facets to its approach: it is philosophical, methodological, and praxis-oriented, particularly within the fields of anthropology. Here at Savage Minds, we have decided to take these questions on again in a different public, and work through a series of dialogues, debates and possibly even reconciliation. Continue reading